What connects rotting fish, ninja hand postures, and American race riots? That’s right: sushi!

Though it’s exploded in popularity in the last few decades, this iconic food has a long and fascinating history. In fact, the image of ‘sushi’ that’s almost certainly in your mind right now is only around a century old; a fraction of the thousands of years people have been eating and enjoying older types of sushi.

And though it’s said in Japan that it takes 17 years to become a true sushi master, it’ll only take 15 minutes to read all about the rich history of this iconic Japanese dish.

The beginning

The origins of sushi stretch so far back that they are slightly shrouded in mystery. What we know for certain is that at some point over 2,000 years ago, people in what is now Southern China began pickling fish with salt. This was borne out of necessity, for without refrigeration fish wouldn’t keep; in fact, other cultures developed similar ways of preserving their catch: the infamously unpalatable Swedish surströmming has recently gained internet fame – and though it only dates from at least the 16th century, there is evidence of fish fermentation in Europe dating back over 9,000 years.

What was perhaps different in Southeast Asia, however, was how the fish were caught. With the advent of wet-field rice farming (probably around the Mekong river) the rainy season could leave a vast excess of fish in the rice fields – a bounty that needed to be preserved. The result was fish meat covered in a slimy substance – caused by the digestive enzymes of the fish breaking down tissue – which could be scraped off before eating. Delicious!

The Chinese character for pickling fish in salt (si 鮨) appeared in Chinese dictionaries sometime between the 5th and 3rd century B.C. It’s possible that the Han Chinese picked up the technique from non-Han peoples as they moved south. By the 2nd century A.D., a new character had appeared: sa 鮓, which referred to a new technique of preserving fish: pickling it with salt – and then fermenting it with rice. This was the true original form of sushi, known as nare-zushi.

Nare–zushi, which literally means ‘aged sushi’, was a long process. Fish were gutted, salted, and stuffed with (or placed in) cooked rice, and the mixture left to ferment in a barrel for around a year. After the lacto-fermentation was complete, the rice would be discarded and the fish eaten.

Entry into Japan

Throughout their ancient history, the areas that are now China and Japan engaged in rich cultural exchange. Through physical immigration and the spread of information, the latter island received many new technologies and ideas from the continent: from rice cultivation, to Buddhism, to nare–zushi. In fact, the introduction of wet-field rice farming to Japan almost certainly overlaps with that of nare–zushi.

Though Japan is now known for its (supposed) homogeneity, at this point it did not exist as a nation state – unification was centuries away. So it’s no surprise that regional variations on nare–zushi developed. According to sushi historian Ole G. Mouritsen, the most widely known form was funa–zushi, which was first prepared over a millennium ago in what is now the Shiga prefecture. ‘Funa’ is a golden carp common in Lake Biwa (near Kyoto), which was caught and salted, then soaked in water to remove excess salt, then placed in cooked rice under pressure and fermented for over half a year. As usual, the rice was discarded and only the fish eaten.

Developments

Of course, it seems a shame to waste all that precious rice – and our predecessors thought so too. Also, contemporaries such as the 12th century writer Konjaku Monogatarishū make it clear that the smell of nare–zushi was terrible – regardless of taste.

By the 14th century, people in Japan had started opening the fermentation barrels earlier – after a few weeks instead of months – and were eating the rice as well as the fish. Because of the lactic acid produced by lacto-fermentation, the rice had a distinctive sour taste; a taste similar to that of rice vinegar.

Rice vinegar had been around in Japan for at least as long as sushi. In fact, some of the earliest recorded references to sushi and rice vinegar both date to the 8th century: the 718 Yoro Code (Yōrō-ritsuryō) notes sushi being paid as tax, while in 794 a document claimed that certain warriors used rice vinegar as a tonic to give them power and strength (though I suspect the only thing that actually gained ‘strength’ was the smell of what came out the other end…).

Whether for strength, taste, or convenience, rice vinegar began to be widely used in the preparation of sushi during the Muromachi period (1333-1568) – though the rice vinegar industry would not really take off until the following Azuchi-Momoyama period (1568-1600). One new technique involved adding the vinegar to the rice to hasten fermentation. Nama-zushi (or nama-nare, ‘half fermented’) involved eating raw or partly raw fish wrapped in the vinegared rice.

Another type of sushi using rice vinegar was invented (or at least popularised) by an Edo (now Tokyo) doctor, Matsumoto Yoshiichi, in the mid-18th century. To prepare haya-nare-zushi, rice vinegar would be added to cooked rice, treated fish placed atop, and both pressed under heavy pressure. After a roughly 24-hour process the result was ready to eat, and the vinegar adequately mimicked the sourness of the lactic acid produced from longer fermentations.

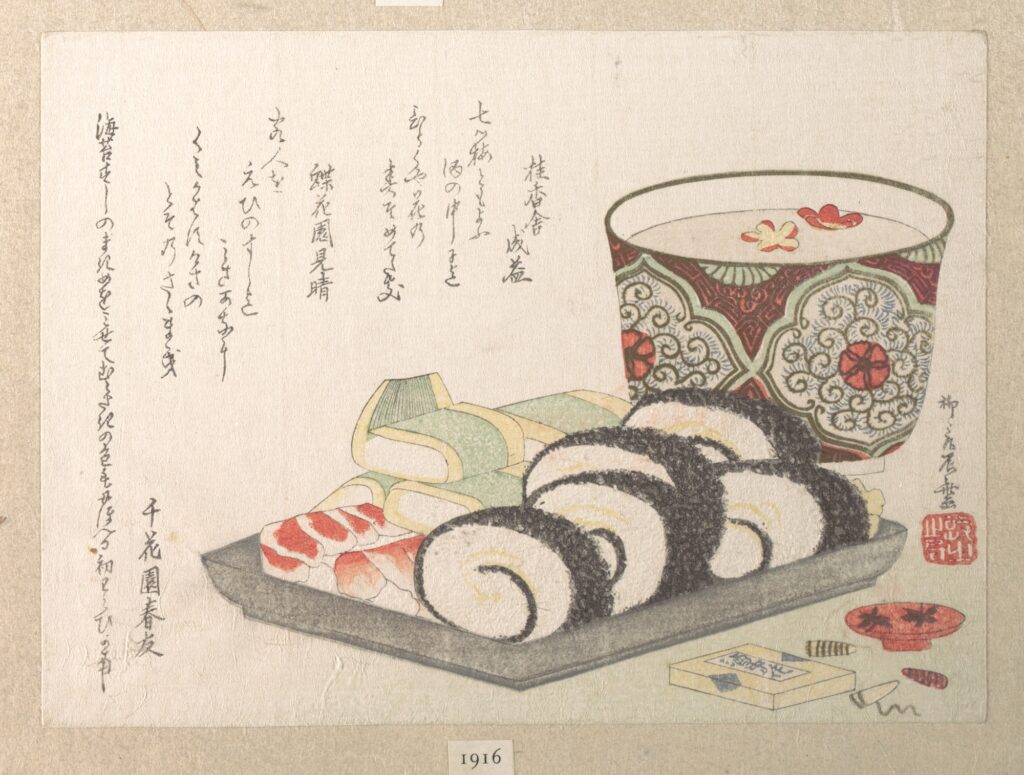

A similar technique also developed in Edo was hako-zushi, in which the vinegared rice and filleted fish would be pressed in a small wooden box, and the resulting block cut into small slices to serve.

Modern Sushi

By the final decades of the Edo period (1600-1868) the process of preparing sushi had thus been refined to take only a few hours. But it wasn’t until 1824 that Edo resident Hanaya Yohei is said to have invented the modern form of sushi: nigiri-zushi. Freshly cooked rice would have rice vinegar and salt added, be hand-packed into small portions, fish placed on top, and the result immediately eaten. The fish might be fresh, but early forms of nigiri-zushi often used fish that had been cooked or marinated in soy sauce or vinegar, or fish that had been salted. (Again, the lack of fridges still presented a fundamental obstacle to the popularisation of truly raw fish sushi.) One contemporary author who wrote under the name ‘Sailcloth’ described the hand position used in this squeezing method as ninjutsu – a reference to a hand position used by ninja, in which the index and middle fingers of the right hand were held in the palm of the left.

In this form, sushi was a food for the masses – an early ‘fast food’. During the 19th century, Edo was prone to fires; to stop their spread, sections of houses would be knocked down, and during the rebuilding process flocks of workers needed quick and simple food to keep them going. Men also wandered the streets of Edo selling nigiri-zushi from boxes carried on their backs.

Perhaps the most iconic and popular way to get nigiri-zushi, however, was the sushi stall. These began to pop up all around Edo from the mid 19th century, and were also aimed at the masses: in the evening, the proprietor would wheel his stall into place; he would request some water from nearby houses to dip his fingers in (which would have to last him all evening – not particularly sanitary…); he would have his cooked rice ready in a wooden box; to keep his feet dry, he would sit down to make the sushi. Having placed his wares in an ice box for freshness, and after setting out a bowl of soy sauce and another of pickled ginger on the counter, he would hang up his noren (a sort of decorated banner), which would signal that he was ready and open for business. Customers would be mostly men, returning home from the bathhouse, or an evening of business (or pleasure…). They would stand to eat, and dip their sushi into the sauce with their fingers – but no worry, for the noren was handily there for wiping; indeed, a well dirtied noren was seen as a sign of a good (or at least popular) sushi cart.

In 1923 – ten years after the advent of refrigeration – the Great Kantō Earthquake devastated Tokyo. This not only sent nigiri-zushi chefs all over Japan, but began the process by which stalls became shops. Initially, these indoor areas were chiefly used as convenient places to wait while your order was prepared by the owner, who still worked at his stall, which was parked outside. Stalls stuck around until shortly after the Second World War, when the Allied Occupation Authorities decreed their end.

Sushi goes worldwide

There is a common belief that sushi only became popular in the U.S. in the 1960s and 70s, when hippies, Hollywood residents, and/or health nuts (depending on who you ask) became obsessed with it. And while that may have been the moment sushi truly went mainstream in the West, America – and indeed the world – had already been fascinated with and enjoyed sushi for decades.

The West had been, at the very least, vaguely aware of sushi since they first made sustained contact with Japan. In a 1603 Portuguese dictionary, for example, there is an entry for nama-zushi. However, that changed after Commodore Perry forced Japan to open in 1853-4.

Initially, Japan still forbade its residents to leave, so knowledge of the country and its culture – including sushi – came from Western visitors. In particular, hundreds of American Protestant missionaries, invigorated by a religious revival at home and the untapped potential of unconverted souls, went to Japan. And whether in person or through missionary publications, they sent back information on this new country to fascinated readers at home.

Indeed, the late nineteenth century saw something of a craze for Japan – particularly in America, but in Europe and elsewhere too. Japonisme, the obsession with Japanese arts, was one result; another was the addition of the country to the ‘grand tours’ of the wealthy. Even former president Ulysses S. Grant stopped off in Tokyo during his world tour. It seems the interest went both ways, for he later recalled that his reception in the capital was unmatched by any other on his trip – the Meiji emperor even broke tradition by shaking his hand! James McCabe’s bestselling 1879 account of this tour, A Tour Around the World by General Grant: Being a Narrative of the Incidents and Events of his Journey, mentions the party’s encounter with ‘a series called sashimi. This was composed of four dishes and would have been the crowning glory of the feast if we had not failed in courage. But one of the features of the sashimi was that live fish should be brought in, sliced while alive, and served. We were not brave enough for that…’

By then, Japanese were permitted to emigrate. In fact, the year before McCabe’s book hit the shelves, the Prescott Arizona Daily Miner reported the opening of a ‘Japanese Restaurant’ in the town – that is, a place owned by Japanese and serving American food. According to them, “Jap” was known for good food at cheap prices. By 1905, Americans were regularly eating at Japanese noodle houses, where one could get a bowl of what was essentially ramen for only a nickel.

If the second half of the nineteenth century saw Americans growing ever more enamoured with Japan and the Japanese, the opposite was true for the Chinese. Having immigrated to the West Coast in search of jobs during the gold rush, American anti-Chinese attitudes culminated in the 1882 exclusion act, which banned Chinese immigration.

Though this nasty brand of American nativism would eventually result in the Japanese being excluded informally in 1907 and formally in 1924, in the 1880s they were still widely liked by Americans – in fact, they were often directly and positively compared to the Chinese. It was thus after the latter were excluded that the numbers of Japanese moving to the states truly began to take off.

The the twentieth century began with great promise for Japanese-American relations – not least in regards to sushi. In fact, Americans were so interested in sushi at this time that H.D. Miller labels it the ‘Great Sushi Craze’! Though many, like Grant’s party, were not brave enough to try raw fish, others were eager to try a staple dish from this exciting new culture. Indeed, Japanese dinner parties were apparently all the rage. In 1905, for example, a Mrs M.H. Jewell and Mrs F.L. Conklin served the members of their Monday Club a Japanese Meal ‘in true Japanese style—the guests being seated after the Japanese fashion, on cushions on the floor….’ On the menu: sushi, of course. And this was in North Dakota!

In 1906, a recipe for sushi was published in various newspapers across America: ‘“Sushi” is made by boiling a half cup of rice with two tablespoons of chopped preserved ginger. When cold mold into cakes about two inches long and one inch wide, flatted on top. Cut up a half pound of any kind of fish into narrow strips, boil, then add a small bottle of sho-yo [soy sauce], which is a sauce to be obtained at a “Jap” store. Cool the fish and serve a strip on the top of each rice cake.’ Another recipe also sent out that year advised would-be sushi chefs to slather their creations in mayonnaise – ah America, trust you to take the health out of a famously healthy food…

Sushi gets the other American treatment: nativism

Sadly, this didn’t last. From around 1905, anti-Japanese attitudes began to spread throughout the West Coast. This nativist sentiment was initially most popular amongst workers who were being outcompeted by the Japanese. Japanese restaurants were one target of anti-Japanese anger: in 1907, a group of union men caught some fellow workers eating in one such establishment, and the resulting brawl spiralled into a looting and destruction-filled riot that lasted several days and inspired newspapers on both sides of the Pacific to call for war.

The same year, President Teddy Roosevelt concluded the so-called Gentleman’s Agreement with Japan, which was intended to essentially bar Japanese working-class labour from the U.S. After World War One, however, the anti-Japanese sentiment had spread beyond the American working class, and became part of a general wave of ugly anti-foreign attitudes that culminated in the Immigration Act of 1924 – which effectively banned Japanese immigration (as well as severely limiting that from other ‘undesirable’ countries). Within a decade, the U.S. and Japan really were at war – a war that historians rightly term a race war; that is, one in which the enemy is a particular race. Of course, this led to the horrors of internment, and – of much less consequence, but relevant here – an effective end to American (and allied) interest in sushi.

Comeback Kid

Obviously, you know this wasn’t really the end for global sushi. In the decades after the war it has continued its spread around the world – recognisable almost anywhere, with uncountable variations, it nevertheless remains attached to ‘Japan’.

Sushi is still somewhat a food of the worker – if you’re willing to risk the gas station or convenience store – but is also a luxury food, and even a whole affair. In fact, in Japan its actually more of a special occasion dish. There, it takes at least five years to become a trained sushi chef; some practice for a considerably shorter period and go international, where standards might be slightly lower. Though the chef now stands and the customer sits, the noren often still hang outside (if the place is open – though I wouldn’t recommend wiping your hands on it), and the process of finger-packing the nigiri still happens before your eyes. Indeed, sushi connoisseurs recommend taking a place at the bar, where you can watch the chef work, and – if you’re brave enough (culinarily and monetarily) you might not even order anything in particular, instead letting the chef surprise you.

When the sushi arrives, it might include food models made from soft plastic – now popular in restaurants around the world, they originated in sushi shops, where they were used to hold and present certain ingredients. Depending how fancy you’ve gone, you might also find a variety of other decorations – such as carved aspidistra leaves, which are used to separate different kinds of sushi when arranged in a combo, or to decorate particularly fancy pieces of sushi.

In general, the sushi of today consists of this formula:

- rice with vinegar

- tane – something on top

- akami – red or dark tane (such as salmon or tuna)

- shiromi – white tane

- hikari–mono – shiny tane (such as mackerel)

- nimono–dane – tane that have been cooked or simmered (such as octopus or eel)

- hokanomono – all other tane

- gu – something inside – that is, everything other than the rice in rolled sushi.

You can find good sushi all over the world—in fact, it’s easy enough to make at home! There are a ton of great recipes and tutorials online, but I’d recommend starting with maki-zushi: all you need to do is place a sheet of nori seaweed on a bamboo rolling mat, spread a thin layer of cooked sushi rice on top (making sure to wet your hands so the rice doesn’t stick to you), and place your desired gu inside. It can be whatever you want, so get creative! Just make sure not to overfill, and leave about an inch of seaweed empty at the top so you can overlap it with the bottom when rolling the whole thing together. Then take a sharp knife—getting it slightly wet can help stop sticking—and slice up your rolls. You’ve now got a perfect chance, when dipping (or dunking) in soy sauce, to practice your chopstick skills—but could always just use your fingers. I won’t judge—and if anyone does, just tell them that’s how they used to do it in the old days!

Of course, you might be thinking: reject modernity—embrace tradition. How do I get my hands on some of the cool/wacky/fun older variations of sushi? Well, if you’re really feeling brave—or you’re stuck at home (Corona, anyone?)—you can always try and make it yourself… but many older types of sushi can still be found near the places where they were developed. So the stinky nare–zushi can still be had around Lake Biwa; han-nare is still eaten in Wakayama; Haya-nare is still had in Osaka, Nara, and Kyoto, and each place has their own unique spin—for example, in Nara the sushi might be wrapped in persimmon leaves; and, of course, you can get edo-mae-zushi in the place where truly modern sushi all began: Tokyo.

So – delicious, infinitely varied, and (depending on what you add) healthy – that’s sushi. Have you tried it? If not, perhaps this Japanese saying will inspire you: when you taste something delicious for the first time, especially the first fresh produce of the season, your life will be prolonged by 75 days. So go try some sushi!