110 years ago, a subscriber to the San Francisco Call wrote in to the paper with a seemingly simple question: ‘What is the Shinto religion of the Japanese’?

From the forced opening of Japan in 1854 to the present day, the nature of Shinto has gripped the West. Western scholars were eager to discover an explanation for the characteristics of its people and culture. Many of their questions are still asked today—and many of the incorrect answers they spread are still told in reply. Is Shinto uniquely Japanese—can only Japanese people follow it, or even understand it? How does it coexist with Buddhism, Confucianism, and other beliefs? Is it really a religion at all, or something else?

The history and exact nature of the set of beliefs now called ‘Shinto’ were the subject of intense debate in Japan centuries before the West arrived. Hardly surprising, considering that they were shaping and influencing individuals in Japan long before the formation of the Japanese state. [hardacre]

The true answers to these questions are complex. Some of them lack a clear answer at all. Take the last one: while most people call Shinto a religion, scholars aren’t so sure. The various beliefs that we call Shinto have changed throughout history—to say nothing about regional variation. Is it really useful to use the term ‘religion’ when considering Shinto at a particular point, or as a whole? What makes something a ‘religion’, anyway?

Shinto doesn’t have a founder. There is no single creator god, nor a unifying holy text that sets out beliefs or activities. In fact, the beginnings of Shinto are so ancient and shrouded (due in no small part to the lack of writing in Japan at the time) as to be a mystery. What there are, however, are legends—myths that tell how Japan and the Shinto gods were created…

MYTH

Thousands of years ago, before the land was created, there were twelve invisible deities. The last two, Izanami and Izanagi, were directed by the others to solidify the drifting flotsam and jetsam on the sea.

‘Izanagi and Izanami stood on the floating bridge of Heaven and held counsel together, saying, “Is there not a country beneath?” Thereupon they thrust down the jewel-spear of Heaven and, groping about therewith, found the ocean. The brine which dripped form the point of the spear coagulated and became an island which received the name of Ono-goro-jima.

The two deities thereupon descended and dwelt in this island. Accordingly they wished to become husband and wife together, and to produce countries.’

— Sources of Japanese Tradition, Vol I

After a brief argument caused by the female deity having the nerve to speak first (the horror!) the two deities united their sources of masculinity and femininity and became husband and wife. They then birthed the islands of Japan: from Ō-yamoto no Toyo-aki-tsu-shima (Yamoto) to Tsukushi (Kyushu) to the thousands of other isles in the slightly misnamed ‘Great Eight-Island Country’.

‘Heaven and Earth first parted … yin and yang then developed; and the Two Spirits [Izanagi and Izanami] became the ancestors of all things. … So, in the dimness of the great commencement, we, by relying on the original teaching, learn the time of the conception of the earth and the birth of islands; in the remoteness of the original beginning, we, by trusting the former sages, perceive the era of the genesis of deities and of the establishment of men.’

— Sources of Japanese Tradition, Vol I

From Izanagi and Izanami came the other gods. Principal among them was Amaterasu, the Sun Goddess, whose magnificence caused her parents to send her to Heaven at once. Later came Susa-no-o, the Storm God; his unruly temper killed many people and plants, and his parents chastised him as wicked and sent him to the Nether-land.

Before leaving, Susa-no-o ascended to Heaven and spoke with Amaterasu, and from opposite banks of the Tranquil River of Heaven they swore to produce children. Begging Amaterasu to hand him the jewels in her headdress, Susa-no-o ‘crunchingly crunched them’ [Kokiji] and produced five male deities from his mouth. Amaterasu claimed these as her own, as they had come from her ornaments. It was from these men that the imperial family descended: from the ‘Heavenly Sovereign Kamu-Yamoto’, otherwise known as Jinmu, the first human emperor, all the way to the present day.

At least, so claim the two great native chronicles of early Japan. The Chronicles of Japan (Nihongi or Nihon Shoki) and the Records of Ancient Matters (Kokiji) were written in 720 and 712 C.E. respectively. The Records recount the story of Japan from the Age of the Gods to around 500 C.E., with the Chronicles covering the same story but continuing until the end of the seventh century. Sadly, as you probably guessed, there isn’t much in the way of reliable historical fact anywhere—bar the last century or so of the Chronicles.

The Records were commissioned by the imperial house of Emperor Temmu, and were seen even by contemporaries as hugely biased towards the ruling Yamato clan. The Chronicles, written by a committee of scholars instead of just one, were created to redress this claimed bias.

According to Mark Cartwright, the Chronicles contain the first textual instance of the word ‘Shinto’. Indeed, both works have often been hailed as containing the ‘original deposit’ of Shinto folklore. But as the team behind Sources of Japanese Tradition point out, both the Records and Chronicles are ‘late complications’ filled to the brim with ‘political considerations and specifically Chinese conceptions’. (You might have noticed, for example, the explicit mention of ‘yin and yang’ in the quotation from the Records above.) Ironically, they were actually produced in response to the growing influence of T’ang China; the importation of Chinese culture and systems of government were undermining the legitimacy of the Japanese emperor and aristocracy, whose claim to rule lay in tradition. This foreign influence also sparked a renewed interest in native culture—similar to what happened during the Westernisation of the nineteenth century.

Before the introduction of Chinese writing—and, therefore, Chinese ideas—the Japanese could not have written down their religious beliefs, in the very unlikely case they even had an articulate body of doctrine to record. As Sources notes, even the great Neo-Shinto scholars of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries tried ‘almost in vain to find in these texts any evidence of pure Japanese beliefs.’

ORIGINS

So where did Shinto come from, then? And when did it begin?

The simple answer is: no one knows for certain. However, we have a good idea.

Even underneath the politics and foreign influences there are hints in the early texts at the origins of Japan’s ‘national faith’. The mythic world of the Age of the Gods is polytheistic—many gods rule in counsel; it is nature oriented; and it is alive, in the words of Sources, with a ‘riotous creativity and irrepressible fertility.’ You might have noticed these features in the short quotations above.

Perhaps, then, instead of being ‘founded’ or ‘created’, Shinto evolved from a collection of earlier beliefs?

By the time Japan came into the view of Chinese historians—and therefore entered into written history—it was the first century B.C.E. Unfortunately the Chinese histories make no mention of how the place they called ‘Wa’ was peopled by those we now call ‘Japanese’. What they do describe is a land filled with over a hundred barbarian tribes.

Interestingly, early Chinese accounts describe several characteristics of the Japanese that still make up stereotypes today: ‘honesty, politeness, gentleness in peace and bravery in war, a love of liquor, and’—most importantly here—‘religious rites of purification and divination.’

ainu

Now, you’re probably thinking of a specific type of person when you read ‘Japanese’—a person of the Yamato ethnicity, who make up the majority of Japan’s current population. But those early Chinese scholars allude to over one hundred tribes. Who were the others?

Actually, despite the stereotypes about ethnic homogeneity, the Yamato are by no means the only ethnic group in Japan. They weren’t even the first to arrive. ‘Jōmon’ is the name given to the various peoples indigenous to the Japanese archipelago. They migrated to the Japanese archipelago from a variety of different places over 15,000 years ago, and lived there until around 300 BCE, the end of the Jōmon period. Genetic studies have shown that only a very small percentage—perhaps 10%—of Yamato Japanese ancestry comes from the Jōmon. The rest comes from a different people, the Yayoi, who arrived from China and Korea sometime around the end of the Jōmon period and displaced the Jōmon people already there.

In fact, the very term ‘Yamato people’ only came into use around the 19th century, as a way to distinguish its members from the various ethnic minorities living inside the empire of Japan’s borders. Many of these indigenous communities called their part of what is now Japan home for millennia—and some continue to do so.

The Ainu are perhaps the most famous example. Like the Yamato, their origins are unclear, but they probably descended from an indigenous population that once lived in northeast Asia. Originally they lived in an area that stretched from the north of the main island, Honshu, to the northern Kuril islands, now claimed by Russia. However, as the influence of the Yamato spread, the Ainu were pushed back to Hokkaido, which they called Ainu Moshiri—the Land of the Ainu. Unlike the Yamato, genetic studies suggest that something like 65-80% of the ancestry of the Ainu people comes from the Jōmon peoples who lived in Hokkaido.

Hokkaido was eventually colonised by the Yamato. After the Meiji Restoration in 1868, perhaps taking inspiration from Western imperial powers, Japan began to systematically discriminate against and marginalise the Ainu. These indigenous people were stripped of their names, language, and traditions. The government promoted the myth of an ethnically homogenous Japan to further its imperial ambitions. Small steps in the other direction have been made recently—for example, in 2019 Tokyo finally recognised the Ainu as an indigenous people. However, many activists say this legislation still does not go far enough. The vast majority of Ainu people still hide their identity—or have no idea, the knowledge lost over the generations.

Back at the turn of the first millennium, what impact did this cultural diversity have on Shinto? Naturally, each of the tribal communities in the land of the Eastern Barbarians had its own cultic beliefs and practices. Some might be focused on fertility; others were shamanistic or animistic; others worshiped nature, their ancestors, or certain heroes…

Over time, as Japan centralised, the distinctions between these cults began to disappear, combining to become the earliest forms of what we call Shinto. So, for example, the Sun Goddess could be the chief deity of a nature worshipping cult and a cult that worshipped its ancestors and a giver of fertility and a blesser improving the fortunes of the nation—and so on.

Nevertheless, the diversity of Shinto’s origins continued, even as the central government began to increase its control in the seventh century. Natural features—such as the mountains noted by the early Chinese historians—contributed, as did a strong regionalism that continues (to a degree) to the present.

But what were—or are—the deities worshipped by the people of early Japan? They certainly weren’t anything like the God of monotheistic religions; perhaps better to use the Japanese term, kami.

However, kami is a tricky term to truly understand. Even the famous eighteenth century student of Shinto, Motoori Norinaga, admitted that he did not ‘yet understand the meaning of the term kami. In general, however, it may be said that kami signifies, in the first place, the deities of heaven and earth that appear in the ancient records and also the spirits of the shrines where they are worshipped.’

To the ancients, kami included anything that was ‘outside the ordinary, which possessed superior power, or which was awe-inspiring’, according to the modern scholars writing the Sources of Japanese Tradition. That includes animals, plants, seas, rivers, mountains… even humans! The sacred emperors are the most obvious example; they were actually also called ‘distant kami’ to signify the degree of separation between them and the commoners revering them.

They weren’t the only ones though—not by a long shot. Any human could potentially become a kami: the Age of the Gods is known as such because the humans of that time were all kami. In fact, most of the kami of that divine age were humans.

Though they aren’t necessarily accepted throughout Japan as a whole, each region and local area has a variety of human kami.

Interestingly, the Ainu word for deity or spirit is kamui. Notice the similarity? The Ainu have a wide range of beliefs and rituals, as well as a rich oral tradition filled with Yukar (sagas of heros), Kamui Yukar (stories of the gods) and Uwepeker (old stories). Though few Ainu know their historic language—a legacy of colonialism—there are efforts being made to preserve it.

Kamui/kami is not the only vocabulary-based similarity between Ainu and Shinto traditions. Tama means ‘soul’ in both, while ‘pray’ is nomi for the Ainu and nomu in Shinto. There are also similarities in ritual: for example, in late June many Shinto shrines hang up a Chinowa, or woven grass ring. By passing through the ring in a figure of eight—a ritual or exorcism called Chinowa Kuguri—one can be protected from ‘crime, affliction, disasters and plagues’. In Ainu culture a similar ritual is conducted to heal illness, although they pass under an arch of leaves and grass instead of walking through a hoop.

These similarities aren’t a coincidence. However, while some vocabulary might have been borrowed from Japanese, Ainu belief is not really an offshoot of modern Shinto. One legacy of racialised colonial thought is the assumption that primitive cultures must have taken from more civilised ones. Thus William George Aston, in his 1907 study of Shinto—‘the ancient religion of Japan’—notes the similarities with the religion of the ‘savage race’, the Ainus. Of course, he finds it ‘reasonable to suppose that … the less civilised nation … borrowed from its more civilised neighbour and conqueror.’ And eight years earlier the Japanese government had passed a law effectively denying the existence of the Ainu, calling them ‘former aborigines’!

In reality, as Segawa Takurou notes, mainland Japan and Ainu cultures are more like an extended family. They both evolved from the variety of cultic beliefs swirling around amongst the various ‘barbarian’ tribes discussed by those early Chinese scholars. If anything, the Ainu are actually the main family, retaining more of the character of the Jōmon Japanese—while mainland Japan has been more heavily influenced by other customs, such as Chinese.

Now, it’s important to note that kami (and kamui) do not have to be good… evil, mystery, and raw power can be just as extraordinary and awe-inspiring as virtue.

It’s easy to see the influence of nature. The rivers, mountains, and oceans of Japan are certainly awe-inspiring—both in their beauty and in their danger. The same supposedly heaven-sent winds—or kamikaze—that are said to have saved Japan from Mongol invasions in 1274 and 1281 have destroyed coastlines and continue to sweep away hundreds of lives. Indeed, in 2018 and 2019 Japan was the 1st and 4th country in the world most affected by extreme weather.

SHRINES

It is important, then, to avoid causing offence and suffering the wrath of nature. Kami, like nature, are everywhere. When disturbing their domain by digging, planting, or other such activities, it is only natural to therefore ask permission, give offerings, and construct a place for the spirit to receive them or to dwell in. These places are the shrines (jinja) of Shinto.

An area without a shrine is unfit for human habitation, according to Shinto, because no proper relations have been established with the local kami.

Originally, shrines were not really constructed per se—instead, they would be natural formations, such as a cave, forest grove, or waterfall. Rites were performed outdoors. Rock altars might also be used.

Eventually, worshippers began constructing buildings as shrines. The earliest, ancient accommodations were single dwelling houses built for ancestral spirits. This influenced the first constructed Shinto shrines, which housed not only deified historical heroes but any local kami.

Architecturally, early Shinto shrines were very simple: usually just a single room, occasionally partitioned, which was raised off the ground and accessible from steps at the side or front. Wood was the only material used—including whole tree trunks for beams. That meant no mud, no clay, no metal—so no nails. Walls and roofs were thatched, as Berkeley’s Office of Resources for International and Area Studies explains:

‘Thatching consisted of either the barks of the Japanese Hinoki or miscanthus or thin wooden plates, and the ridges of roofs [were] made of wood in the shape of a box. The roofs, which shed Japan’s heavy rainfall, [were] built up in a delicate curve from strips of Hinoki bark and then trimmed. The forked timbers on the roof are called chigi. The short logs lying horizontally across the ridge of the roof are called katsuogi.’

These buildings served as a place where the kami could be worshipped. This earliest style of architecture can still be seen in the main building at the Grand Shrine at Ise (Ise Jingū), the most important shrine in Shinto. It was here, east of Kyoto, that Amaterasu, the Sun Goddess and most important deity in Shinto, was first enshrined. She is still believed to dwell here, in what is called the ‘soul of Japan’. In fact, this is the only place where you can see this style of shrine—by law, no other shrine can imitate it.

Before the shrine was built, Amaterasu was worshipped in the form of the Hinoki or Japanese cypress. Legend holds that sometime in the fourth century C.E. Princess Yamatohime-no-mikoto left Nara and wandered for 20 years; eventually she heard Amaterasu’s voice, telling her that this spot in the forest was where the deity wished to be permanently enshrined and revered.

Historians think that the Shrine was actually first built sometime in the fifth century—though as mentioned, Japanese history isn’t particularly reliable before the sixth century. We do know that the current design of the Shrine was first constructed in 692 C.E.

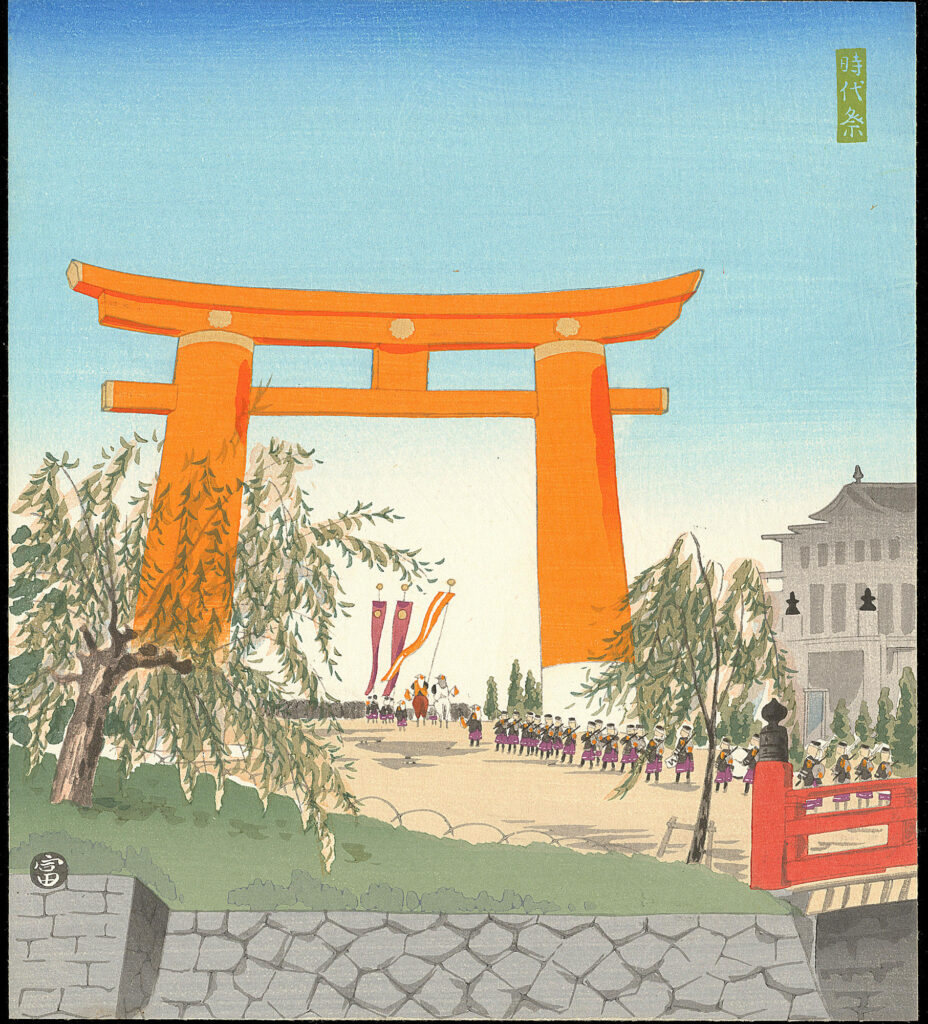

As Shinto became more established in early Japanese society, shrine complexes were built to make it easier to access kami and worship them by conducting rituals. In addition to the hall housing the kami, there were often other ceremonial buildings, and large complexes might have multiple kami enshrined in different halls. By the medieval period it was common to have complexes surrounded by fences, with a torii gate or sacred arch at the entrance. The sacred torii gateway separated the sacred from the external world. Worshippers would go into the haiden and direct their prayers to the nearby honden, which housed the kami—often in the form of a sacred object.

Today the shrine at Ise is a huge complex—about the size of central Paris! In fact, today Ise hosts two complexes: the Inner Shrine (Naiku), dating from the third century and dedicated to Ameterasu, and the Outer Shrine (Geku), dating from the fifth century and dedicated to the grain goddess.

What’s unique about the shrine at Ise is that from the eighth century onwards 16 of the 125 buildings in the complex—as well as the Uju bridge and Torii gateway—are completely rebuilt every 20 years. With a long pause during the chaos of the Warring States period in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, the Shrine has therefore been torn down and rebuilt 62 times. Each time the old materials are sent to be used in other shrines around the country. In an adjacent plot to the torn-down shrine, a pole of the sacred wood Hinoki is planted and enclosed in a simple hut. The premises are also cleansed and purified. This symbolic cycle of impermanence last occurred in 2013, and the current structure is due to be dismantled in 2033.

The most sacred object housed in the shrine is the yata no jingi, or mirror, which is the manifestation of Amaterasu. It is one of the Three Imperial Regalia. This mirror is an example of the practice of representing resident kami through symbols or sanctified objects. At Tomakamai Shrine a paper or cloth strip attached to a stand represents another example of such a ritual object. They are known today as gohei: most often a pair of paper or metal strips, each ripped in four places.

(image: ‘Gohei in front of Shinto shrine’)

According to the Chronicles, the Three Imperial Regalia—mirror, sword, and curved jewel—were brought down from Heaven to Izumo by Amaterasu’s Divine Grandson, Ninigi-no-mikoto; he was also the great-grandfather of the first human emperor, Emperor Jimmu. The mirror, sword, and jewel are supposed to represent the three values required to rule: wisdom, valour, and benevolence respectively. Interestingly, examples of these objects—the bronze mirror, long sword, and curved jewel—were found earlier in north China and Korea. That is, they are of continental origin. Originally, as Sources explains, they did not represent native tradition but were objects of a ‘higher’ civilisation, used to bring power and legitimacy to the Yamato dynasty over the surrounding tribes. What was unique—or at least different from Chinese conceptions of dynastic sovereignty—was the fact that the legitimacy of the ruling house was shared with supporting clans and corporations. Their ancestors received orders from Amaterasu just as the ruling dynasty’s did.

(image: ‘Conjectural images of the Imperial Regalia of Japan.’)

In legend, the ‘eight-hand mirror’ that came to emblematise Amaterasu at Ise was originally used by the deities (along with a host of other items, including the sacred jewel, and techniques) to coax the Sun Goddess out of a cave. She had fled there, casting the land into darkness, in indignant anger because of Susa-no-o’s antics, which included scaring her by throwing a flayed colt into her sacred weaving hall.

The Records also give Susa-no-o credit for finding the sword. After defeating an eight-headed serpent that was terrorising a family of deities in Izumo, his sword broke while chopping up the beast; searching inside, the deity discovered the ‘Herb-Quelling Great Sword’, which he gave to Amaterasu as an apology for having offended her before.

While Amaterasu’s shrine at Ise is the most important, the most ancient shrine (built by humans, anyway) is the one in Izumo. Called Kitsuki-no-miya, it is dedicated to the sun of Susa-no-o. Because of its grand age, it is also called ‘the shrine ahead of those to all other gods’.

This shrine is known for symbolising union and compromise; a visit is seen as particularly good for those seeking marriage or wanting better harmony in their family. Perhaps this is because it was here that Susa-no-o (of the Yamato line) married the Izumo princess, and where their son Prince Plenty or the Great Landlord God married a Yamato princess. Though the joining of two ancient lines certainly symbolises unity, the latter marriage was anything but harmonious…

According to the Chronicles, Prince Plenty, the new husband of Princess Yamato, was never seen in the daylight, only coming to visit her at night. Dissatisfied with this, the Princess asked her husband to stay past dawn so that she might see him, and he agreed to stay in her ‘toilet case’ the next morning. He warned her not to be alarmed at his form, which unsettled the Princess. The next morning Yamato opened her toilet case and was shocked to see a beautiful little snake; her frightened exclamation shamed the God, who changed to human form and declared that he would cause his wife shame in turn. And so he left, ascending Mount Mimoro. In a gruesome end, the Princess—looking up at the empty space where her husband had left and filled with remorse—‘flopped down on a seat and with a chopstick stabbed herself in the pudenda (that is, the outer part of her genitals) so that she died.’ Unless you’re sure your partner isn’t a snake, it might be worth trying one of the other shrines that promote marital and familial harmony…

It’s worth noting that this story implies the existence of ancient snake worship in Japan. Indeed, as mentioned, literally anything could be a kami—from animals to mountains. One mountain kami you’ve probably heard of is the most famous in Japan: Mount Fuji.

It’s not hard to see why the people of ancient Japan would deify this majestic mountain. The faith of Mount Fuji is old—very old, in fact. A story in the Hitachi no kuni fudoki tells of an ‘ancestor kami’ that requested lodging for one night from the kami Fuji of Fuji-dake—that is, from Mount Fuji. From the end of the Heian Period the faith combined with Shingon esoteric Shugenō practice, a Buddhist sect. Climbing became an expression of faith: legends recount famous figures who made the climb, and by the Muromachi period (1336–1573) there were regular pilgrimages up the mountain. Mandala paintings of these journeys were produced to encourage people to make the climb, and the mountain was preached about by some as a utopia. In the Edo period followers of the cult would make ‘Fuji mounds’ in their local area and climb them instead of the mountain itself. Others ventured into the mountain’s ‘Womb Caves’—a network of pockets and tunnels left by centuries of eruptions—to experience ritualistic death and rebirth. This is just one example of how certain cults, beliefs, and practices have maintained a distinct characteristic despite a thousand years of centralisation.

The Hitachi no Kuni Fudoki—literally ‘fudoki of Hitachi province’—is one of several fudoki that have survived, at least in part, to today. Fudoki is the name later given to books produced in the Nara period (710–794), which described a specific region’s climate, culture, traditions, myths, histories and so on. Hitachi no Kuni Fudoki was presented to the court by the Government Office of Hitachi Province in the early eighth century.

Alongside the Chronicles and Records, fudoki are one of the main sources used by scholars searching for evidence of early Shinto beliefs. Like the two major texts, however, the fudoki were also influenced by Chinese conceptions—in fact, the genre of fudoki containing the legend recounted above was of Chinese origin.

The fudoki were compiled under the ritsuryō system. Kami worship was given an important place in this system—hence the effort put into recording and compiling the legends and histories of all the local kami in each region.

CHINA AND BUDDHISM

The ritsuryō was a legal code adopted in the mid-seventh century. The Japanese court wished to establish a centralised government in the style of their influential Chinese neighbour, the T’ang dynasty. The three or four centuries in which this code was influential is therefore called the ‘Ritsuryō Era’.

So: the very centralisation that began to blur the lines between the various pre-Shinto cults was heavily influenced by Chinese ideas—especially the philosophies of Confucianism. This is why some scholars argue that ‘Shinto’ can only be identified once other belief systems were imported. Like how scholars of philosophy, race, and psychology have argued that the ‘other’ is necessary for the formation of the self, perhaps these foreign ideas—Confucianism, Taoism, Buddhism, and so on—were crucial in marking the lines around what would be called ‘Shinto’ belief.

As stated, Kami were given an influential position in the new ritsuryō system. The Council of Divinities (Jingikan) was established, and tasked with conducting rites of state and coordinating regional practices with those in the capital and—importantly—the imperial palace. The Council ruled according to a code of Kami Law (Jingiryō). This law marked a break from previous, more sporadic attempts at centralising and controlling regional rituals. The court was determined to assert religious—and political—control over the provinces.

Kami Law stipulated that twenty rites be conducted every year for the good of the realm. These rites were first set down in the Yōrō Code of 718, which gave the Council of Divinities the exclusive right to worship kami on behalf of the emperor and court. Interestingly, a split at mid-year meant that most of the rites were actually performed twice each year. Most of them were linked to agriculture; others were for warding off misfortune or for purification; some were directed at the Ise Shrines.

The rites of Kami Law were expanded in 872 and in the Engi’Shiki of 927. These later texts specified procedures and offerings for each ceremony, including new ones that had been added to the list.

The Council of Divinities was also tasked with recruiting Shinto priests, and it maintained a register of those it supervised. These priests, who served at Official Shrines, were allowed to dress as court officials, and could carry a wooden staff called a shaku.

These honours were only given to male priests—women were banned. That’s not to say women played no role in Shinto ritual. Quite the opposite. For example, within the Council of Divinities operated mikanko or mikannagi. These women ritualists are thought to have dated from ancient times when kami were not even anthropomorphised. In the Engi’Shiki they are recorded as a regular feature in official rituals. They conducted rites for the 23 kami who protected the emperor and the realm, and in the eighth and ninth centuries they purified the emperor’s body. Over time gender-based distinctions increasingly restricted women to performative roles—shrine maidens selling amulets, grounds cleaners, ritual dancers for certain deities, and so on. Though virtually unheard of before the Second World War, in recent decades more women are becoming priests.

(Image: ‘modern female priest’)

Helen Hardacre is one of many scholars who identify the ritsuryō system as institutional origin of Shinto. Others, however, point to the almost complete absence of the term ‘Shinto’ in both everyday language and official documents of the time.

Though Kami were thus given an important role in the system, Buddhism was also. All the major political players in East Asia had by this time adopted Buddhist rites—Japan followed its allies and neighbours. This actually caused much controversy in the court, as those with roles performing kami worship resented this blow to their power and prestige. However, they were defeated, and Chinese influence intensified.

Because a separate group was created to administer Buddhist matters, Hardacre points out that the Council of Divinities could be seen as a keeper of ‘indigenous’ tradition. Or, rather, the court used a rhetoric of indigeneity to distinguish kami ritual from Buddhism.

However, after the ritsuryō system dissolved at the end of the tenth century kami worship changed again. Buddhist influence expanded and some kami were amalgamated with Buddhist bodhisattvas to create single deities. Some images of Buddhist figures were incorporated into Shinto shrines, and some Shinto shrines were managed by Buddhist monks. Buddhist temples were attached to local Shinto shrines, and both included worship of kami and buddhas. You can see this combination for yourself today: at Osaka’s Shitennō-ji Temple, for example. First built in the late sixth century by Prince Shōtoku who was trying to promote this new belief system called Buddhism, some identify it as the oldest Buddhist temple in Japan. If you go to Osaka to see it, you’ll be able to see the Shinto stone torii gate that marks one entrance into the complex.

In the seventeenth century, a term was coined to describe this combination: Shinbutsu-shūgō, literally ‘amalgamation of kami and buddhas.’

Remember how the first chronicles were influenced by Chinese ideas and culture? Well, one of the most important of those ideas was Buddhism, as well as Taoism and Confucianism. Buddhism had arrived in Japan by the sixth century, well before the first word was written about Shinto.

Indeed, the seemingly-impossible difficulty of discerning ‘true native’ Shinto lies in its fundamentally syncretic nature. That is, just as the old beliefs we describe as ‘Shinto’ appear to have been formed through the combination of various cultic practices, they also included in that combination a host of other ideas, many of which came directly from China.

Shinto and Buddhism were so intertwined for so much of Japanese history that some historians hesitate to even try and separate them into distinct religions—at least, until the Meiji state did just that in the 19th century.

But assuming they were distinct, how did they coexist so well? One factor might have been a different focus. Shinto was always far more concerned with the present: life, marriage, birth, and so on. It was practical, all about improving life in the here and now. Buddhism had more to say about death, and what happened afterwards.

That’s not to say Shinto had nothing to say about those mysteries. Though the funerary ceremonies were simple and there was no concept of life after-death or reincarnation, households did build altars dedicated to the deceased. They are still used, and are called kamidana. These altars are usually oriented towards the east or south, where they will receive more light. They’re easily distinguishable from Buddhist altars: Shinto ones are higher and ornamented with paper gohei; Buddhist ones have doors.

Kamidana honour the ancestor kami of the family (and are sometimes used for worshipping the god of the home); after death the individual’s soul (tama) could influence the world, and they would keep a particular interest in their family, guarding and protecting the household to ensure continuation of their family lineage. Here we see the influence of ancient ancestor worship on Shinto: reverence and respect for ancestor kami was, and remains, a major part of Shinto belief and ritual. Though Buddhist and Shinto funeral rites differ, they both result in the soul of the deceased transforming into or joining the collective kami of that individual’s ancestors.

Offering incense, flowers, or food to family ancestors is a daily activity. However, O-bon—sometimes called ‘Japan’s Day of the Dead’—is when ancestor worship takes centre stage. People call the spirits of their ancestors home, honour and remember loved ones with various ceremonies, then guide them back to their resting places. This three-day celebration—for it is a joyous time—is usually held in mid-August, though some regions’ interpretation of the lunar calendar leads them to hold their festivities in July.

O-bon (or just ‘bon’) is the second biggest traditional holiday in Japan, after the New Year. Traditionally, people are given days off to return to their ancestral homes and celebrate with their families. Many activities might take place: on the first day, paper lanterns or fires might be lit to guide ancestor kami home; on the second day, in addition to telling stories about the deceased, communities might perform Bon Odori, traditional folk dances; on the final day the spirits are guided back to their resting places—which might be a grave, but could also just be a body of water, which has traditionally been viewed as where spirits dwell. One festival celebrated by some on this day is Toro Nagashi. You might have seen it—hundreds of candle-lit lanterns floated away on waterways, guiding spirits to their home, with the ocean at the end of the route…

The Bon Odori comes from the Buddhist story which forms the basis of this festival. Like many myths from East Asia, it involves a son who, through filial piety and various offerings, manages to help his deceased mother, who was trapped in the Realm of Hungry Ghosts. His happy dance upon seeing his mother relieved was the Bon Odori.

If you’re going to visit Japan and want to experience this traditional festival, be warned: there are taboos. For example, if you stay out too late, you might just bump into one of the ghosts walking the streets… and don’t even think of trying to take a photo with it—or anything, at night!— because even if you manage it before you’re abducted, all you’ll manage to capture are some bad spirits.

The eighteenth century Shinto scholar and theologian Hirata Atsutane elaborated more on where exactly the souls of deceased Japanese went. He claimed they remained eternally in Japan, staying in the area of their grave and serving the nation in the realm of the dead. This realm could not be seen by the living; it was (or is) a realm of darkness, separated from the present world. However, ‘darkness’ was not literal—the realm had light, houses, food… His proof? The numerous accounts of people returning from the realm of the dead, and the accounts of miraculous occurrences in the vicinity of graves.

The ancient myths and legends do tell of a more literal land of darkness: Yomi. Also known as Ne-no-kuni (Land of Roots) and Soko-no-kuni (Hollow Land), it was said to be a place beneath the earth where the souls of the dead gathered.

Yomi, outside of some myths, really has limited significance in Shinto. Life—the present—is the most important thing. No Shinto textual source explains who goes there and why, and there is no concept of punishment or reward for souls after life; if there is any suffering in Yomi, it is merely the separation from loved ones still living. In fact, some suggest that the very concept of life after death as suggested by Yomi was only introduced with Buddhism.

Nevertheless, there are said to be two entrances to Yomi: one is where all the seas plunge down, and the other is… a hole blocked by a boulder in Izumo.

Huh? Well, remember Izanami and Izanagi, the deities who created the islands of Japan? According to one myth, while giving birth to Kagutsuchi, the fire god, Izanami was terribly burned. Her tears of pain produced many other gods, but she eventually died. Izanagi, distraught, headed down into Yomi to bring her back, but as she had already eaten something in the Hollow Land she could not leave. Nevertheless, she pled with the gods to make an exception, and begged Izanagi to not look at her. Similar to Orpheus, however, Izanagi looked—and saw that Izanami had already started to decay. Horrified, he fled (or was chased by monstrous beings) and plugged the hole he had entered through, sealing her (and the terrors) inside.

After catching his breath, Izanagi performed a cleansing ritual in the river Woto to rid himself of impurities. During this, numerous gods were born—including Amaterasu (from when he washed his left eye) and Susa-no-o (from when he washed his nose).

This is sometimes said to have inspired the key Shinto practice of cleansing before entering a sacred space.

This ritual is called temizu or chōzu. The worshipper approaches the chōzu–ya or temizu–ya, a pavilion containing the chōzubachi, which itself contains water. Using a dipper or water ladle, the left hand is washed, then the right, then the mouth, and finally the handle of the ladle. After performing this ritual, the worshipper can now move on to the main shrine.

You’ve probably seen people do this—or forget to do it, depending which Youtubers you follow. This cleansing ritual is only one of many in Shinto. They are collectively called O–harai, and are used for cleansing in both a physical and spiritual sense. Most important, perhaps, is removing tsumi—pollution or sin—and kegare, which is more specifically a state of uncleanliness brought on by contact with certain unclean things or acts. Death, childbirth, menstruation, and rape are all examples of things that will result in kegare, which then must be removed through purification rituals.

Cleanliness is an extremely important aspect of Shinto and Japanese life in general. You’re most likely already aware of this—think about how you have to take off your shoes before entering a house or shrine, or how you must shower before bathing.

Indeed, Shinto and Buddhism were both quite practical. When Buddhism was first introduced to Japan it was viewed by many as a new tool or technology; a system that could be used to ensure wealth, protect the nation, and so on. Similarly, many Shinto rites and rituals were practical solutions to particular problems.

One example of this is the norito: prayers or mantras uttered on ritual occasions or festivals. Many are collected in one of the major early texts used by scholars of Shinto, the Engi-shiki. Compiled in 927 C.E., it consisted of 50 or so books of Shinto laws and rituals. It reflected the increasing codification of Shinto practice, in line with the unification and bureaucratisation of the Japanese state.

Most norito that are preserved are formulaic, ritualised, and repetitive. Typically they included and invocation of a deity or multiple deities, a recollection of the founding of the shrine that was the site of the ceremony, an identification of the individual reciting the norito and their status, a list of the offerings being given, a petition for the desired blessings and benefits, a promise to compensate for those boons, and a finishing salutation.

Many norito were very specific about the deities, places, and details of local history (or myth) concerned. For example, the Sources of Japanese Tradition includes one called ‘The Blessing of the Great Palace’, which was used to ensure the gods’ protection of the Imperial Palace. It was recited by a member of the Imbe clan, who were professional abstainers; abstention (or self-denial) was closely connected to ideas of purity. You might remember Amaterasu’s weaving hall, defiled by Susa-no-o—one translation implies that it was a sacred place of abstention and purification.

Another norito, called ‘The Great Exorcism of the Last Day of the Sixth Month’, detailed a list of ‘heavenly’ and ‘earthly’ sins and called on a group of deities to sweep them away. Heavenly sins are often linked with the behaviours that might anger kami: from covering up ditches or double planting to skinning backwards or defecating. Interestingly, the sins are not all moral—some are just a result of bad luck. So while cutting living flesh and violating a mother and child—your own or another’s—are earthly sins, so are certain insect bites and white leprosy.

When the sins appear, the norito goes:

‘By the heavenly shrine usage … Pronounce the heavenly ritual, the solemn ritual words.’ The purification will remove all the sins: ‘They will be taken into the great ocean / By the goddess called Se-ori-tsu-hime … When she thus takes them, They will be swallowed with a gulp, By the goddess called Haya-aki-tsu-hime … When she thus swallows them with a gulp, The deity called Ibuki-do-nushi, Who dwells in the Ibuki-do, Will blow them away with his breath to the land of Hades, the under-world … Beginning from today, Each and every sin will be gone.’

Not all kami were so helpful. One norito, called ‘Driving Away a Vengeful Deity’, is a ritual reenactment of a group of deities consulting on how to deal with deities disturbing Japan. The solution: gifts, offerings, and persuading the deity in question to move. Cloth garments, weapons, jewels, rice, wine (sake), animals, herbs, fish and seaweed… ‘I place these noble offering in abundance upon tables / Like a long mountain range and present them / Praying that the Sovereign Deities / Will with a pure heart receive them tranquilly … And will not seek vengeance and not ravage, / But will move to a place of wide and lovely mountains and rivers, / And will as deities dwell there pacified.’

Hopefully, of course, you would have built a shrine and established proper relationships with your local kami. The influence of buddhism on Shinto shrines can be seen architecturally: curving roofs, corridors instead of fences around shrines, four- or eight-post gates instead of simple torii, metal and wooden ornaments with similar motifs to those in Buddhist temples, and healthy doses of red paint. When Buddhism was being popularised in the Nara period, the design of the ancient Izumo shrine was changed; its roof was curved and Chinese-style ornaments added. A central pillar is said to represent the stick supposedly used by Izanagi and Izanami to stir the oceans and create the islands of Japan. The patronage of powerful clans like the Fujiwara—who dominated the nation during the Heian period (794–1185) and remained influential for centuries after—resulted in some of the most resplendent shrines. Influenced by the grander style of Buddhist temples, nobles constructed them to demonstrate the honour and power of their families.

MEDIEVAL JAPAN

Over the centuries, Shinto continued to evolve in combination with Buddhism, as well as other beliefs. Many specific cults and schools emerged during this time, each with their own specific beliefs and rituals. Their beliefs were based in the idea that kami were manifestations of Buddhist deities. For example, the earliest of these school, Ryōbu Shinto (Dual Aspect Shinto) combined Shinto with the Shingon sect of Buddhism. Developed during the late Heian and Kamakura periods, it connected Amaterasu and the Great Sun Buddha, Mahāvairocana. In turn, Ryōbu Shinto influenced the formation of other schools—such as Sannō Ichijitsu Shintō (One Truth of Sannō Shinto), which combined Shinto with the Tendai sect of Buddhism and flourished in the Tokugawa period (1603-1867). Furthermore, schools like Ryōbu Shinto often split into multiple branches over the years.

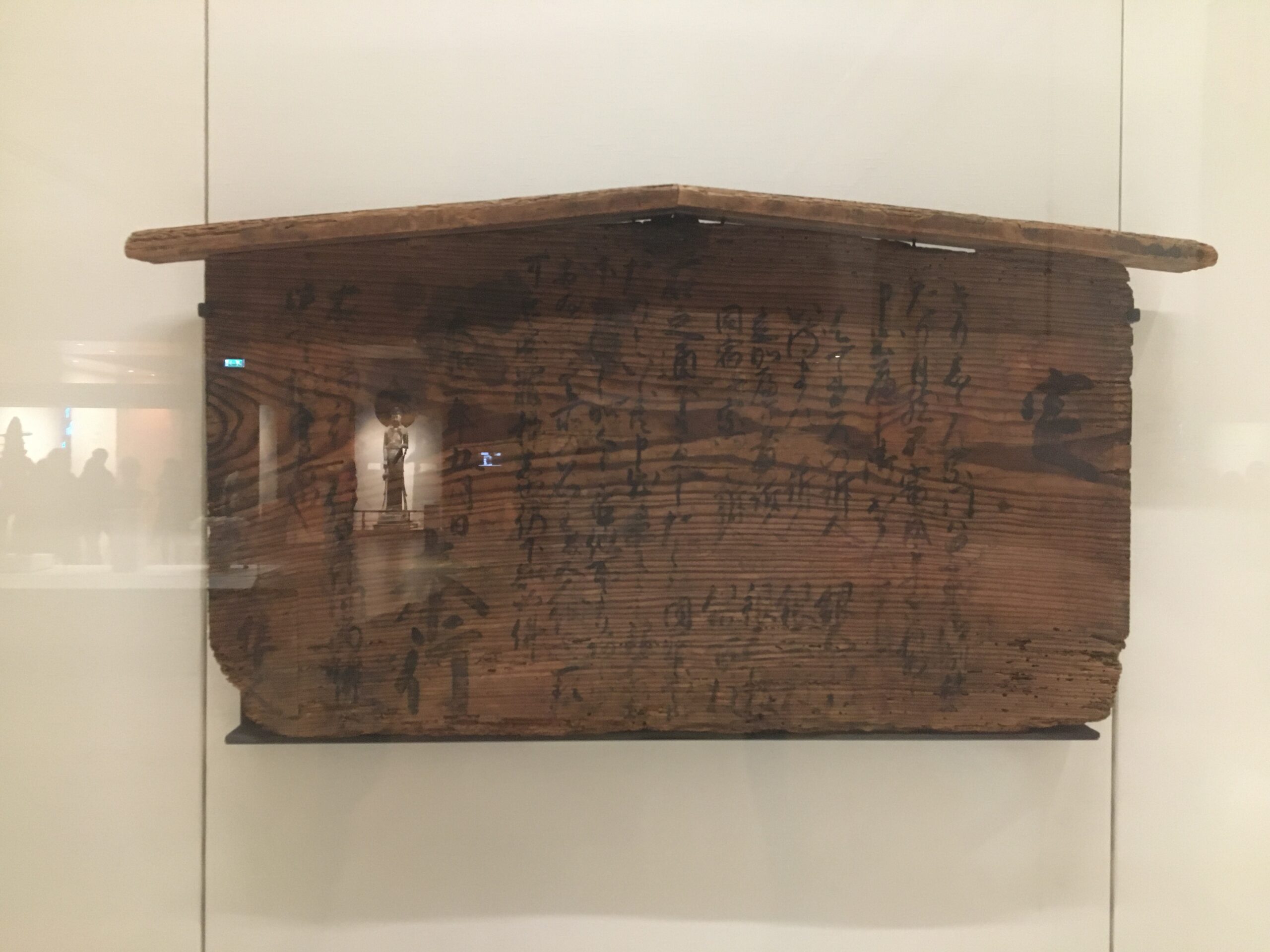

It was during the Medieval period that Christianity reached Japan. Portuguese Catholics arrived in 1549, intending to start a church. Though welcomed at first, in 1614 samurai authorities banned the new religion. This was connected to the general policy of isolation, where Japan closed itself off from the world. The only Europeans allowed in the country were employees of the Dutch East India Company, who were themselves restricted to Nagasaki. Throughout the seventeenth century, multiple anti-Christian edicts were passed. One notice board on display at the British Museum was originally posted in 1682 and details the rewards that could be claimed for handing over Christian priests, believers, and sympathisers. ‘If someone appears suspicious’, the Magistrate reminded, ‘you must report them.’ Up to 500 pieces of silver could be earned for turning in a priest or an important Japanese sympathiser or believer.

(Image: British Museum)

Nevertheless, Christianity still influenced Japanese belief, including Shinto. Its influence on modern Shinto organisations and Kokugaku are important but rarely discussed.

Kokugaku (National Learning) was a scholarly movement in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Its followers aimed to shift the focus of Japanese scholarship away from the dominant study of Chinese, Confucian, and Buddhist texts towards Japanese classics. Some of the major early students of this school of thought are believed to have been influenced by Christianity. The movement eventually sought to eliminate all foreign influences, culminating in the Fukko (Restoration) school of Shinto. This revival of Shinto as a supposedly pure Japanese belief would really take off just a century later.

STATE SHINTO

In 1868, everything changed. Japan was newly opened up to the world and the Meiji Restoration had begun. After parading the new emperor from Kyoto (the ancient capital) to Edo (the new capital), the new government embarked on the project of building a modern nation state. The nation builders recognised the potential in Shinto, so the first thing they did was issue ‘separation edicts’ to separate it from the other belief systems with which it had coexisted for centuries—primarily Buddhism.

The importance of this separation is often overlooked. Allan Grappard even calls it ‘Japan’s ignored cultural revolution’. You could argue that this is the moment where Shinto as a distinct religion truly began—in fact, the image of Shinto as a distinct, purely Japanese religion held by all Japanese people since ancient times is to some degree a tradition that was invented by the Japanese Meiji State during this period.

The process was intense. Ritual implements considered ‘Buddhist’ were catalogued and removed from buildings designated ‘Shinto’, and vice versa. Priests had to choose between being Shinto and Buddhist.

Buddhism had fallen out of favour. It was attacked and persecuted, often with accusations of corruption and waste—critiques that had been leveraged for over a thousand years.

Meanwhile Shinto enjoyed privileged status in the government. On one hand, this was a reaction to the rapid influx of western technology and culture. Many feared that Japanese culture was in danger of being forgotten, so they sought to affirm it by identifying and promoting ‘native’ ideas and customs—such as Shinto.

On the other hand, the new government had some big ambitions. They saw the nationalistic white nations and their colonial empires; witnessed what happened to their traditionally more powerful neighbour, China, at the hands of European imperialism. To avoid the same fate, Japanese leaders argued that Japan had to stake its claim to join the table of world powers.

Shinto was a powerful tool they could use for nationalistic purposes. Separation from Buddhism was only the start of what is called the Shinto Directive. A national hierarchy of shrines was created, with a unified annual ritual calendar. The government wanted to give all shrines a national, patriotic focus. This was difficult: not only were there tens of thousands of them, each often had very different local contexts. To solve this, from 1906-12 the government merged thousands of shrines so that there would be only one per village. Just as the shrines were converted from local places to part of an integrated national system, the government hoped to turn local people into citizens of a nation. This massive merger occurred alongside secular campaigns, such as the creation of new administrative districts and the Local Improvement Campaign.

This didn’t happen without resistance—many fought to preserve their local sacred identities. To get around the local variation, the government focused on the emperor. He was used as a unifying figure through which every Japanese citizen—no matter how different their regional beliefs and traditions—could develop a patriotic dedication for their nation.

What resulted was a system called State Shinto—a combination of Shrine Shinto (the various shrines around the country) and Imperial Shinto (the rites of the imperial household), as well as the Kokutai (National Polity) Doctrine, which claimed that Japan had a unique state system based on emperor worship that extended back to ancient times. The exact meaning of ‘State Shinto’ as a concept is still debated—for example, some scholars think it should be given a more narrow definition than here, and others think it should be extended to include Sect Shinto and even other religions which were subordinated into a wider ‘State Shinto System’.

Shrines became the connections between the centre and the periphery of modern Japan. Priests were involved in national teaching campaigns. Similar to the formal education system—western-style compulsory education was introduced shortly after the Meiji Restoration—this was meant to develop a strong sense of patriotism and nationalism within students. Ethics classes taught children ‘core values’—though they had their roots in morals common in the eighteenth century, they became seen as part of this mythical ‘timeless’ Japanese culture. The government was attempting to forge a universal Japanese identity, in part on shared common values.

The Meiji government argued that Shinto was inextricable from Japanese identity. It was not something individuals were free to choose to believe in. Some claimed that it was more than a religion—it was a fundamental aspect of a uniquely Japanese consciousness; a ‘nonreligion’ distinct from, and most definitely superior to, all religions. Shinto was therefore a powerful tool with which the Japanese government could discipline its subjects. This was necessary to create a nation—and, crucially, a modern military—that could take on the world.

Remember how I said that many Japanese leaders wanted to become a world power? Well, at the turn of the twentieth century the way to do that was to go to war and acquire some colonies. So Japan went to war with China in 1894; it took them only a year to sweep aside their beleaguered neighbour and in 1910 they officially annexed Korea, adding it to their burgeoning empire.

The use of Shinto as a disciplinary tool was most severe in Korea. Just under 400 Shinto shrines were erected as part of an effort to ‘Japanize’ Korean colonial subjects. Worship at these shrines was required—a stricter obligation than in Japan!

Koreans were also banned from questioning the idea that Shinto was not a religion. Of course, this was strange, as in 1936 a high ranking Japanese official in Korea claimed that the ‘fundamental idea’ of Shinto ‘differ[ed] from that of religion’. He published an article called ‘on the refusal to worship at shrines’, where he claimed that: ‘…from ancient times down to the present the shrines have been national institutions expressive of the very centre and essence of our national structure. Thus they have an influence totally distinct from religion, and worship at the shrines is an act of patriotism and loyalty, the basic moral virtues of our nation.’

The use of Shinto and emperor-worship to develop these ‘basic moral virtues’ had been a controversial topic in America for decades. The first Japanese immigrants to America were received warmly—as was their food!—but by 1905 an organised campaign to have them excluded had begun in California. One of the main arguments used by the anti-Japanese was that people of Japanese descent—even those born in America—could never be loyal American citizens. The anti-Japanese claimed that they remained utterly loyal to the Japanese emperor, the ‘Mikado’. Unlike Western religion, Shinto supposedly lacked morals, and was instead a cult to which all ethnic Japanese belonged. Thus, they were utterly unassimilable; they could not be included in the melting pot.

Remember that subscriber to the San Francisco Call who in 1911 asked what Shinto was? Well, in the answer, the editor said that Shintoism was ‘rather an engine of government than a religion’, which kept ‘its hold on the masses chiefly through being interwoven with reverence for ancestors’.

With this understanding, many anti-Japanese portrayed Japanese immigrants and Japanese Americans as foreign agents. Indeed, Americans viewed Japan’s claims to world power with suspicion and fear. They saw their increasingly industrial—and militaristic—neighbour as a threat. Some wrote to the government accusing Japanese locals of operating military bases, or of acting as spies. Others produced art warning of an imminent invasion. In 1924, the fears of ‘Yellow Peril’ resulted in Japanese immigrants being formally excluded from America.

It would not be long until war between America and Japan did break out. The War in the Pacific has been rightly called a race war, and it worsened the already considerable anti-Japanese sentiment present in much of America. Tropes used in the Japanese exclusion campaign were brought out and exaggerated. Japanese soldiers were often portrayed as animals—inhumanly aggressive and willing to die for their country.

Shinto was blamed for much of these behaviours—the infamous Japanese aggression, nationalism, and suicidal will to die for their country. Therefore, in December 1945 the Allied forces occupying Japan issued the Shinto Directive. The document attempts to distinguish between genuine Shinto religion and the ‘non-religious cult commonly known as State Shinto, National Shinto, or Shrine Shinto.’ The aim was to remove the state-sponsored Shinto-like rituals which had underpinned the military and education, which was achieved through the claim that Shinto was not a religion but a duty—every Japanese subject must be loyal and devoted to the emperor, the descendant of Ameterasu. The occupying powers wanted to implement an American model of separated religion and state and freedom of religion.

The document banned ‘Shinto doctrines and practices [and] also the ‘militaristic and ultranationalistic ideology’ of any religion or creed which asserted the superiority of the Emperor or the people of Japan’ in ‘any publicly-funded or government institution’. A few months later, the Jinja Honcho was established. In English, this means ‘The Association of Shinto Shrines’. It took over many of the centralised administrative and official functions of the government departments that had previously overseen State Shinto. For example, the president of the Jinja Honcho is the one who formally appoints priests to shrines. Along with heads of local offices, the president also undertakes formal visits with offerings to local shrines in place of the emperor or local governors.

Generally, the Jinja Honcho promotes Shinto as a ‘national system of faith and practice’ separate from Buddhism. It holds that all shrines are in a hierarchy with the imperial shrine at Ise at the top. Though there are some independent networks—such as the one in Kyoto—something like 80% of the Shinto shrines in Japan are part of the national network. However, the 1947 Constitution of Japan (nihonkoku kempo) has several articles concerning religion: it prohibits religious-based discrimination; guarantees ‘freedom of thought and conscience’, as well as freedom of religion and the separation of church and state; and forbids the use of public funds for any religious purposes not under the public’s control. Therefore, the Jinja Honcho proclaims no particular Shinto teaching—though, as mentioned, it does affirm the idea of the Ise shrines having spiritual leadership over the rest, on the basis that the imperial shrines are the spiritual homeland of the nation. The Jinja Honcho also supposedly doesn’t claim that Shinto is a superior religion to others—nor is it meant to describe Shinto as a civic duty instead of a religion. However, there is some ambiguity—or even controversy—on these two points. For example, in the Meiji era groups of souls were enshrined together as kami in certain shrines in a ceremony called goshi. Many of these souls are enshrined in special ‘nation-protecting’ shrines (gokoku jinja) or shrines for the spirits of those who died in war (shokonsha). Since the constitution officially separated religion and state, roughly 500 members of the Japanese Self-Defence Forces (Jietai) have been enshrined in goshi ceremonies by Veterans’ Associations. These ceremonies have sometimes even been conducted without the consent of the deceased’s families. The issue lies with whether the ceremony is religious and whether the state—through the Associations, which are basically governmental because the Jietai provide them with support—should be allowed to patronise it.

In 1988, a member of the self-defence forces died in a traffic accident. His widow accused the Veterans’ Association and the Jietai of violating her freedom of religion by performing goshi on his soul—he had already been interred in a Christian church. Though a lower court sided with the widow, the supreme court ruled that while the goshi was religious, the Jietai (and therefore the state) had not been involved in religion by assisting the Veterans’ Association nor harmed any other religion. The court essentially ruled that any individual could not use their freedom of religion to limit another party’s freedom of religion. This opened its own tricky questions: to whom does the spirit of a dead Japanese person belong to? An individual? The State?

You might have heard of the Yasukini Jinja—the shrine that houses the souls of over 2 million Japanese soldiers who died during various Meiji-era conflicts, most notably the Second World War. From the 1890s onwards the shrine became an extremely important focus for patriotic loyalty, in part because the souls enshrined there were paid respect by the emperor himself. Various war criminals were enshrined there, some as late as the 1970s. The Shinto Directive singled out this specific shrine and labelled it a religious institution, and it isn’t affiliated with the Jinja Honcho. Despite all this, Prime Ministers of the right-wing Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) visit the shrine to pay their respects—they claim they do so as private individuals, not as representatives of the state. In the 1970s the LDP government attempted multiple times to have a bill passed to establish state support of the shrine, but failed. Later, in 1985, the LDP cabinet paid formal tribute there; this particularly angered many of Japan’s Asian neighbours, as during the Meiji period the shrine also operated as a war museum celebrating the empire’s activities—including horrific war crimes such as the Nanjing Massacre.

Despite all the opposition, the LDP government still implied that it would attempt to establish a formal tribute at the shrine by the Emperor, cabinet, and Jietai. Prefectural governments have also faced lawsuits because they made donations to the shrine.

Even when they have chosen not to visit Yasukuni Jinja in person, Prime Ministers have often sent a ritual offering called a masakaki tree. Though the shrine celebrates various festivals throughout the year, the most important rites are those held every year in spring and autumn. Fumio Kishida sent a ritual masakaki tree to the shrine on October 17th 2021, the start of the autumn festival. Having become Prime Minister less than two weeks before this, and having called a national election for the end of October, the decision to do so was certainly carefully considered. Unsurprisingly, South Korea expressed its disappointment.

Prime Ministers also visit the shrine in person after leaving office. In fact, Kishida’s immediate predecessor, Yoshihide Suga, visited the shrine on the same day that Kishida sent his offering. It’s been some time since a Prime Minister has visited while in office—the last instance was when Shinzo Abe visited in 2013, prompting South Korea, China, and even the US to express their disapproval. Abe has continued to visit since leaving office in 2020.

Another controversy that perhaps emboldened supporters of the shrine occurred from 1966-1977. The inhabitants of Tsu, a city in Mie Prefecture, accused city officials of acting unconstitutionally by using public funds to pay Shinto priests to perform a ceremony called jichinsai for a new municipal sports hall. The supreme court eventually ruled that the ceremony was so ancient and had been performed so many times that it could be considered effectively non-religious; it also decided that the only religious activity that the state could not be involved in is activity that actually supports or harms any specific religious institution. It also rejected the idea that total separation of state and religion could ever be achieved. It claimed that because religion is so important and common in society, and because the state’s duty is to regulate society, attempting total separation would not only be impractical but actually cause discrimination itself. The court explicitly said that in reality ‘it is virtually impossible to achieve a complete separation of state and religion’.

After the American occupation ended in the early 1950s there was a flourishing of new religions all claiming to have roots in Shinto, Buddhism, and other ‘ancient’ or ‘traditional’ beliefs. The people involved, though, often avoid the term ‘religion’, preferring ‘spirituality.’

The first wave of these are literally called ‘new religions’. Later, from the 1970s, there was another wave called ‘new new religions’. This more recent group of beliefs were generally more depressive, often containing a sense of impending doom.

However, one common theme in many of these new religions—and in Shinto itself—is the theory of Vitalism. That is, the idea that salvation lies in this life. That individuals are empowered to change their lives through self cultivation.

SHINTO TODAY

Perhaps that is why Shinto—and religion in general—is still so important in contemporary Japan. If religion is a way to change and improve one’s life, or to respond to situations that demand religious actions, then it is only natural that it be used.

That’s also why Shinto continues to coexist so well with other beliefs, especially those from China that it evolved with for centuries. A common saying holds that Japanese people are ‘born Shinto and die Buddhist’—another claims that they marry Shinto, live by Confucian ethics, and are buried and their soul transformed to their ancestors by Buddhist ritual. Well, why not use the religious tools available for your benefit, in this life and after?

In fact, most surveys of Japanese religion find that the number of ‘believers’ is usually more than double the actual population of Japan. Those taken in by the myth of a ‘pure’ Japanese religion are often surprised when they see, as an extreme example, people talking to Santa Claus and then writing wishes on Shinto ema tablets inside a Buddhist Temple.

Today, then, what exactly is Shinto? Is it a religion? If so, how many people follow it?

Despite the overlaps, Shinto has a distinct identity. The roughly 100,000 shrines that cover Japan are identifiable through their distinct architecture. They are staffed by 20,000 priests and 1,900 priestesses in traditional dress, house a variety of deities that all fall under the term kami, and are the site of rituals and ceremonies that share a common language.

Official statistics claim that over 100 million people participate in this shared language, engage in Shinto activities. That’s over 80% of Japan’s population. But does that make them ‘Shintoists’? The vast majority of those surveyed reject this term. In fact, the majority of Japanese people say they have no religion. Perhaps this is due to the nature of translation: shūykō, the term usually used to mean religion, has come to be associated with organised religion. Though many participate in the shared language of Shinto, few regard it as a religious identity. As scholars of Shinto John Breen and Mark Teeuwen point out, the average patron of Shinto shrines has only a vague concept of Shinto. It is therefore functionally impossible, for example, to distinguish between a ‘Shintoist’ and a ‘Buddhist’, as people in the West might distinguish between more doctrinal religions.

This is not to say that Shinto is unimportant. Quite the opposite. Over 80% of Japan visits shrines on New Years. In one survey almost 90% said they regularly or occasionally visited the graves of their ancestors.

Shinto’s importance can also be seen in the fierce debates about its meaning and purpose. In 2000, for example, they even forced the prime minister to retire!

One aspect of Shinto that remains contentious is whether it is uniquely Japanese. Can foreigners follow Shinto?

The 1,500-odd shrines established in Japan’s empire were mostly disbanded after the end of the war. However, Shinto has still spread around the world, to some degree.

In some instances, this was due to Japanese emigration. For example, there are a few shrines in Hawai’i and Brazil—unsurprising, considering that the U.S. and Brazil are the two places outside Japan with the most Japanese speakers.

Ogasawara, an early proponent of exporting Shinto worldwide, believed that international shrines should deify local spirits and ancestors as the first step of integration into organised Shinto as a whole. In 1928 he visited Japanese emigrants in Brazil as part of this mission. Suga Kōji describes how some settlers resisted; in Aliança, a Japanese settlement in Brazil, Ogasawara’s attempts to convince them to construct a Shinto shrine were rejected and even mocked. On the other hand, in Promissão, established a decade earlier by a man with no special training in Shinto, there was a shrine that housed the ancestral spirits of the native tribe who a had lived their before the Japanese founder’s arrival.

In the last few decades, international interest in Shinto as something beyond academic study has been increasing. In 1986, for example, the first Shinto shrine in mainland America was constructed. Tsubaki America Shrine was established in Stockton, California, by the 96th High Priest of Tsubaki Grand Shrine in Mie, Japan. The Shrine in California is a branch of the Grand Shrine, which is one of the oldest in Japan. Six years later priests of the Tsubaki shrine in Stockton enshrined four kami in a new shrine in Colorado. The same year, another shrine was established in Washington.

Each part of the original wooden shrine in Stockton was brought from Japan. In this humble garden shrine were enshrined five kami: ‘the Kami of Pioneering, The Kami of the Sun, The Kami of Harmony, The Kami of the Land of America, and the Kami of Source of Life.’

However, in Japan the picture is a little different. As in much of the world, there are widespread fears of decline. In part, this is due to a Japanese scholarly focus on what Marilyn Ivy calls ‘discourses of the vanishing’. An imagined past—as recent as last century or as far back as times of legend—contains some ‘pure’ Japanese essence which has now been lost.

Of course, this idea that there was something ‘pure’ to be lost is flawed. If we even accept the existence of ‘Shinto’ as a distinct system before the Meiji Restoration, it has clearly been evolving for centuries, assimilating ideas and practices from other belief systems it contacts.

On the other hand, Shrine shinto especially is genuinely in trouble. There are many more shrines than priests, and a 2007 survey found that 26% of shrine priests had no successors. Shrine income is often not enough for priests to survive on.

These are problems are not necessarily unique to Shinto. Neither are the worries about rationalisation, loss of traditional knowledge, decline of the family unit, and disintegration of communities.

Of course, the shrines and their rites are also potential sources for community building. The festivals especially are an opportunity for people young and old to come together in a way that is increasingly unique in the modern world.

Like that curious San Franciscan 110 years ago, you might consider Shinto unique. In many ways it really is. Hopefully this overview of Shinto has answered some of your questions. Though it was certainly more detailed than that offered by the San Francisco Call, it could never cover all the intricacies of something as complex as Shinto. So I also hope that your curiosity has been piqued, and that you continue to explore Shinto—academically or otherwise!