KYOTO

Explore the thousand-year history of Japan’s greatest city

When you think of Japan, what comes to mind? Perhaps it is the arts—calligraphy, painted scrolls, woodblock prints, or even anime. Or maybe you picture noble men in samurai armour and painted women in rich kimonos. You might think of the intricate tea ceremony, the Kabuki or ancient Noh theatrical forms, or even the sweeping roofs casting shadows under magnificent palaces and traditional townhouses.

If you thought of any of these things, then Kyoto is a must see. For most of its history, it was simply called Miyako (The Capital), and the word ‘Kyoto’ literally means ‘capital city’—which makes sense when you realise that for the last 1,200 years it has been the cultural and spiritual capital of Japan. Indeed, it is sometimes called the Thousand-Year Capital. Left mostly untouched by bombs during World War II, this rich history is still there for you to see and experience first hand. And it is rich—in fact, Kyoto is also called the City of a Thousand Temples, and has more than any other city in the world. With over 17 UNESCO world heritage sites, it is no wonder that Kyoto has been called the most beautiful place to visit in Japan. It was even recently voted as the best city in the world—multiple times in a row!

Kyoto is Founded

Though it is likely that humans have lived in the area around Kyoto for over 10,000 years, the city was only founded by Emperor Kammu in 794. It was not his first choice—ten years earlier, wanting to escape the growing influence of Buddhist clergy in the capital, Heijō–kyō (now Nara), he moved the capital to the newly-constructed city of Nagoaka–kyō. He might have moved again because of frequent flooding and disease; or perhaps he was afraid of the spirit of his brother, who had died while being exiled for the murder of the new capital’s administrator.

Clearly, his first choice for a new capital had been wrong. But how was he to avoid similar disasters? Early Japan was heavily influenced by its powerful neighbour, China. Countless ideas, items, and innovations came to Japan from the land where the sun set—as one early Japanese king put it. In fact, the Buddhism that had so taken hold in Nara was one such import; Confucianism was another. Central to Confucian thought was the idea of a natural order, where human actions could greatly effect the harmony of the universe. The universe had Three Realms—Heaven, Earth, and Humankind—and there were three sciences developed to deal with events in these realms: astrology, the art of discovering fate; geomancy, the art of arranging buildings to ensure success; and the art of ‘avoiding calamities’.

Emperor Kammu used these sciences to ensure success. In a valley, with what was considered the proper number of rivers and mountains, the area that would become Kyoto was the most auspicious place to found a new capital. Indeed, Heaven—nature—had created that site specifically for a capital; constructing one there was only fulfilling what was intended. Of course, it helped that the site was practically good too, with easy river access for trade and a high water table for wells. The new city was constructed according to the rules of geomancy to further ensure its success. It was modelled after the ancient and fabled Chinese capital Chang’an (now Xi’an). Following yin-yang theories, it was built in a square shape, with eight streets and nine avenues. Construction started with the Imperial Palace (Kyoto Gosho) at the north of the city; standing at the end of the main road—Suzaku Oji (now Senbon-dori)—it was visible from almost anywhere, and was surrounded by ninefold walls. To the south stood the Rashōmon gate. The northeast—an unlucky quarter—was protected from negative influences by a Buddhist monastery which stood on the nearby Mount Hei. This monastery was actually founded in 788 by a young monk called Saichō. Like Emperor Kammu, he had also left Nara, unhappy with the worldliness and decadence of the Buddhist monks there.

Everything was coming together. By November of 794, Emperor Kammu had arrived in his new capital. Poets called it the City of Purple Hills and Crystal Streams, but he named it ‘Heian-kyō’: the Capital of Peace and Tranquility.

Beauty and Tradition: Kyoto in the Heian Period

The founding of Heian-kyō would mark the start of a new era in Japanese history: the Heian period. Less than two decades later, a succession dispute almost resulted in the capital moving once again, but Emperor Saga resisted this, naming Heian-kyō ‘The Eternal City’. Indeed, for the next thousand years the Eternal City, the sacred city, would remain the home of the Imperial Court—until the Meiji Restoration of 1868, when the emperor relocated to Edo (Tokyo).

The Heian period lasted until the late 12th century. For much of this time, Kyoto lived up to its promise of peace and tranquility, and there was a brilliant flowering of culture. Much of what you might have imagined when you thought of ‘traditional’ or ‘classical’ Japan was popularised or produced in this period. Though Japan was by no means a unified or centralised country, Kyoto was the unrivalled centre of national life. During this time, China was militarily weak, which led Japan to become more culturally independent—a fact expressed in literature and art. A native script was developed to better suit the Japanese language. Great works of writing were produced, from imperial collections of poetry to magnificent prose, such as the Pillow Book and the Tale of Genji.

Considered by many to be the world’s first novel. The Tale of Genji was written by Lady Murasaki, a member of the imperial court. It follows the life of Hikaru Genji—‘Shining Genji’—a talented and handsome prince of the emperor; in particular, his many romances with the ladies of the court. It describes the life of the Heian aristocracy—which was quite small, with only a few hundred main male nobles holding favour at any one time. Kyoto is the backdrop, and many of the places described—shrines, temples, palaces—can be seen and visited to this day. Reading the Tale of Genji, you can imagine what life might have been like, when nobles dressed in expensive kimonos rode tall oxcarts down Suzaku Oji, which at that time was up to 84 metres wide. Of course, like all ancient literature, it might a bit tough to get through—so maybe best to go see for yourself!

One place to start might be the Tale of Genji museum in Uji, on the southern outskirts of Kyoto. You could start at Ujigami Shrine, the oldest Shinto shrine in Japan. The honden at Ujigami—the most sacred building, built only for the use of the enshrined kami (spirit)—is also the oldest example of the nagare-zukuri style in Japan, having been built in the late Heian period. From there, you could walk along the Sawarabi-no-Michi (Early Ferns, named after a chapter in the Tale of Genji), a cobblestone trail that will lead you to the Tale of Genji Museum. There, for only a few hundred yen, you can find explanations of the world of the novel, and explore recreated scenes from the book. It even has a recreated oxcart—though you probably won’t be allowed to ride it (after all, you’re probably not a Heian noble).

Murasaki wrote the Tale of Genji in the early 11th century, the height of the Heian period. At this time, painted hand scrolls called emakimono were starting to become popular. Coming to Japan from India through China at some time during the 6th or 7th century, they were held open at arm’s length and read from right to left. These were expensive treasures popular among court ladies; detailed calligraphy would spell out a narrative on paper dotted with silver and gold, attached to rollers of jade or crystal. There were two main types of non-religious emakimono that still exist today: onnae (feminine pictures) and otokoe (masculine pictures). Onnae were generally romances; in fact, the oldest onnae scroll we have today is the Genji monogatari emaki—the Tale of Genji Picture Scrolls.

Despite this cultural flourishing, the effectiveness of political rule from Kyoto had been gradually declining for centuries. The administration had been set up to closely match that of T’ang China—in the same way that the new capital, Heian-kyō, had physically matched the T’ang capital of Chang’an. But it slowly lost its ability to get the income from the provinces that it needed to sustain itself. At the same time, though the imperial line remained unbroken, real power fell into the hands of powerful nobles—in particular, from the Fujiwara clan—and later senior retired emperors. Acting emperors were, barring a few exceptions (such as Kammu), simply figureheads.

Fire and Fury: Chaos Comes to Kyoto

In 1156, the senior retired Emperor Toba died, and the City of Peace and Tranquility experienced the total opposite. Factional splits in the imperial and Fujiwara families led to the Hōgen incident of the same year: mounted warriors were brought in to Kyoto and there was a short military conflict—the first conflict in the city in 3 centuries. For the first time in the city’s history, there were executions in Kyoto; from then on, head collecting was an important feature of life—the heads were used as proof to collect rewards. Around this time there were also two great fires—in 1151 and 1163—that burned many important buildings to the ground. The next few decades would see more fires, earthquakes, and famines damage much of the city.

This period saw the production of some of the greatest war tales (gunki-mono) in Japanese history. These often featured fictional champions or superheroes, credited with inhuman feats of daring and ability. One example, Minamoto no Tametomo, appears in The Tale of Hōgen (Hōgen monogatari), which tells the story of the events of 1156. Little is known about the real Minamoto no Tametomo, but in the tale he is described as being ‘more than seven feel tall … [exceeding] the ordinary man’s height by two or three feet. Born to archery, he had a bow arm that was some six inches longer than the arm with which he held his horses reins.’ He was ‘unlike a human being’—a ‘demon or monster’. Definitely someone you don’t want to have as an enemy or meet in a dark alley… and indeed, in the story he almost singlehandedly holds off an entire army during a nighttime battle!

By 1180 the faction that had emerged victorious from the Hōgen incident were fighting the Gempei War with their enemies, the Minamoto. This was Japan’s first national civil war. In 1185 Minamoto no Yoritomo led his side to victory, and political power became centred in his headquarters at Kamakura. This marked the end of the Heian period, and the start of the Kamakura.

Kyoto remained the home of the Imperial Court, but it was a capital in a purely ceremonial, cultural, and spiritual sense. Emperors still lived there, but they were largely figureheads; real power was held by the leader of the shogunate or bakufu, called the Shogun—although in reality, many Shoguns were themselves figureheads, controlled by powerful families. After Yoritomo’s death, for example, the Kamakura bakufu was dominated by the Hōjō family. In 1221 Go-Toba, a retired emperor, attempted to eliminate the shogunate in what is called the Jōkyū War—after his failure, the rest of the century saw the balance of real power shift away from Kyoto to the shogunate’s headquarters in Kamakura.

This period marked the emergence of a bushi class consciousness—the sense of warriors as a distinct, separate group. As the warrior-dominated system of authority grew, real power also shifted from absentee landowners in Kyoto to figures in the provinces.

These provincial vassals began to question the need of continued submission to the Kamakura bakufu. By the early 14th century this increasing dissatisfaction was sparked into conflict. In 1321, Emperor Go-Daigo discontinued insei, the practice of retired emperors ruling from their retirement cloisters, and became directly involved in matters of state. Ten years later, he was discovered plotting against the shogunate for a second time; he raised an army and hid the Sacred Treasures—the sword, mirror, and jewel, Imperial Regalia of Japan—in a secluded castle near Kyoto, but the next year the shogunate defeated them and he was exiled to Oki. Interestingly, this was the same place that the Emperor Go-Toba had been exiled to a century earlier, after his defeat in Uji. Emperor Go-Daigo, however, did not stay in Oki for long. He escaped the very next year—1333—and, after Kamakura general Ashikaga Takauji defected to support the imperial side, overthrew the shogunate. This was the Kemmu Restoration. Imperial rule would only last for three years, however—in 1336, after tensions had built back up to breaking point, Takauji defeated Emperor Go-Daigo, who was forced to flee Kyoto. Two years later, Takauji made himself shogun, marking the start of the Ashikaga bakufu.

It is also known as the Muromachi period, from the district in Kyoto where Ashikaga Takauji based his headquarters. Kyoto was once again the centre of real power in Japan. This was the start of real warrior rule—where warriors began to define themselves as rulers. It was such a monumental change, some historians even argue that it is the turning point between classical and medieval Japanese history.

Not everything was resolved, however. Emperor Go-Daigo’s flight from the capital began the Nanboku-chō period, the ‘Era of Southern and Northern Courts’. While Takauji placed an imperial descendant on the throne in Kyoto and established the ‘Northern’ Court in the ancient capital, Emperor Go-Daigo formed the ‘Southern’ Court in Yoshino, a short distance to the south. Interestingly, though it was the Southern Court that eventually ‘lost’, it is now the one that is viewed as holding the legitimate imperial line. In 1392, Ashikaga Yoshimitsu—of the Northern Court—united them both, establishing a single line in Kyoto.

Cultural Explosion: Art, Palaces, and Temples in Kyoto

The next 80 years are known as the Kitayama epoch—a time of stable balance among the power holders in Kyoto. During this period, the warrior class started to develop a new elite culture, different from the court culture that had existed in Kyoto for centuries. Of course, this was partly because culture could be a strong sign that you deserved to rule. The Noh and kyōgen theatre forms both emerged during this time, and remain closely connected—though the serious, solemn Noh differs greatly from the comedic kyōgen. Noh has recently been experiencing a revival, and there are plenty of places to see it performed in Kyoto, from shrines to theatres. Even if your Japanese skills aren’t quite up to scratch, it might be worth it just to experience what UNESCO called an ‘intangible cultural heritage’ of Japan: the elaborate costumes, beautifully carved masks, dance-like movement, traditional instruments and music, and even the carefully designed stage.

Another art, newly introduced from China during this time, was sumi-e, Japanese black ink painting. Other activities popularised or developed by the warrior elites are no doubt what you imagined at the start of this article: the tea ceremony, carefully designed gardens, and flower arrangement. All of these cultural activities were linked by an important new form of Buddhism: Zen.

In fact, the second most visited site in Kyoto was constructed by Ashikaga Yoshimitsu as a Zen retreat and retirement mansion: Kinkakuji, the Golden Pavilion. The only building left of his massive retirement complex, it was built to reflect the extravagant culture of the time: each floor is in a different architectural style, and the top two floors are completely covered in gold leaf. There you can sip tea and admire the building’s gold reflection in a pond that is said to have never gone dry.

Ashikaga Yoshimitsu also constructed Hana-no-gosho, a palace complex so expensive and luxurious it rivalled the emperor’s palace. It became known as the ‘Flower Palace’ because here the ‘King of Japan’, as the Ming Emperor called him, received flowers and trees of every season offered by the provincial military governors (daimyō). Sadly it has not survived to this day, though the Daisho-ji Temple—one of the Amamonzeki Temples, a temple run by nuns of noble women—still stands where it was originally built, inside the former grounds of the palace.

The art of flower arrangement (ikebana, ‘making flowers alive’) actually dates back all the way to the Heian period. Introduced from China, it is said that Japanese people’s love for the art began when Emperor Saga—the successor of Emperor Kammu—picked Chrysanthemum flowers in the garden of his palace and arranged them in a pot. His imperial villa, now a temple, is called Daikaku-ji, and is still standing in Western Kyoto; it was built next to Ōsawa Pond, the oldest artificial lake in Japan, where Heian courtiers would host moon-viewing parties. Today you can attend similar parties hosted on the evening of the Harvest full moon, and imagine the sight of the elegant nobles floating on the pond in their small boats, listening to the koto (Japanese zither) and composing verses appreciating the full moon. If you’re confident in your composing skills, maybe you could try making a verse of your own. If you’re visiting in spring, you can also come for the flower festival—the gardens are full of cherry and plum trees, and there is still a flower arrangement school associated with the temple. Or perhaps you might want to try the practice of Shakyo—copying a text of the Buddhist scripture (a sutra). Used for concentration, calligraphy practice, meditation, it is considered a method for achieving enlightenment. (Good to try it, then, if your moon-appreciating verse doesn’t turn out so well…) The monk Kūkai, who founded the Shingon sect of Buddhism in Japan after travelling in China, advised the Emperor in Kyoto to try it when the capital was in trouble.

Chaos in Kyoto 2: The Great Fire and Warring States

Even the most studious Shakyo could not save Kyoto from the troubles approaching it at the end of this short period of peace. In 1467, during the reign of Ashikaga Yoshimasa, there began a long period of chaos and continual warfare. Known as the Sengoku (Warring States) period, it began with the decade-long Ōnin War, a nationwide struggle over who would succeed Yoshimasa.

This war destroyed Kyoto: the city would not recover for a hundred years, and has not seen such devastation since. In fact, ‘pre-war’ Kyoto refers to the Ōnin War, not WWII. Half of the city burnt down, and many of the magnificent buildings described here—such as the Imperial palace and Golden Pavilion—were destroyed. In fact, some argue that this devastation marked a cultural reset, a shift from the Asian-influenced Heian culture to a more uniquely Japanese culture. Though Kyoto still technically ruled the whole of Japan, in reality they could only control the surrounding area, as daimyō warlords battled for supremacy all over the country.

The chaos of the Sengoku would continue for over a century after the Ōnin War ended. Though much of Kyoto was devastated, you should not assume that cultural development came to a halt. Indeed, the shifts in power away from the capital contributed to the spread of many new cultural activities throughout the country. And even in the ashes of Kyoto, progress was made. In fact, 1467 is also known as the start of the Higashiyama epoch, a second flowering of artistic culture.

Higashiyama culture originated with Ashikaga Yoshimasa, perhaps the greatest promoter of the now-classic cultural pursuits that emerged during the Muromachi. It was centred on Yoshimasa’s retirement pavilion, called Ginkaku-ji (Silver Pavilion)—the word Higashiyama actually means ‘eastern mountains’, which is where the Silver Pavilion is located. Finally built after delays in 1482, it was inspired by his grandfather’s Golden Pavilion. Indeed, by visiting the two pavilions you can see for yourself the difference between the Kitayama and Higashiyama cultures. Where Yoshimitsu’s pavilion glitters brightly in golden sunlight, Yoshimasa’s pavilion was intended to glint softly in the moonlight. In the end, silver was never actually added to the walls, but their dark lacquer coat still reflected silvery moonlight. As Jun’ichirō Tanizaki explained in his work In Praise of Shadows, the visual combination of soft light and dark lacquer is very important to Japanese aesthetics. Today the lacquer is gone—both the Silver and Golden Pavilions have suffered damage from earthquakes and fires started by wars and even mad monks. Nevertheless, restoration has ensured they are still magnificent, and though they are closed to the public, you can stroll through their gardens. The Silver Pavilion boasts a moss garden and carefully maintained dry sand garden called the ‘Sea of Silver Sand’. In the sand garden is a sand cone named ‘Moon Viewing Platform’.

Also standing in Higashiyama is Kyoto’s most iconic monument. As the city burned during the Ōnin War, this landmark—more ancient than the city itself—survived. Yasaka Pagoda and the surrounding Hokan-ji temple complex were originally constructed in the late 6th century by Prince Shotoku-Taishi. They have been damaged by fire, earthquake, and war many times—for example, during an 1179 dispute between followers of Kiyomizu temple and Yasaka shrine. The structure that exists today, however, was built in 1440 by Yoshinori Ashikaga, almost three decades before the Ōnin War began. Most of the temple complex is now gone, but the five-story pagoda remains standing on its hill in the Higashiyama district. It is perhaps the most iconic landmark in Kyoto—a must see. The surrounding area is picturesque, and as you wander up Yasaka-dori towards the pagoda, you might notice the lack of powerlines; they were removed in order to improve the view from the pagoda. Indeed, for only 400 yen, you can go up to the second floor of the pagoda and experience one of the best views of Kyoto. It is particularly pleasant in the evening, and when the nearby cherry blossom is in bloom. Yasaka is actually one of four 5-story pagodas in the city—the others are in temples Daigo-ji, To-ji, and Ninna-ji—but it is the oldest and most famous.

Nobunaga Enters Kyoto to Unify Japan

The chaos of the Sengoku ended when one daimyō—Oda Nobunaga—entered Kyoto in 1568 and initiated his famous campaign to unify Japan. The son of a minor lord, he gradually expanded his influence, eventually becoming powerful enough to exile the Ashikaga Shogun, ending the Ashikaga bafuku. Nobunaga knew the importance of projecting his authority. He rejected the imperial offer of a title and used his own, and was ruthless when dealing with opposing power sources. For example, remember the monastery founded by Saichō on Mount Hei, protecting Kyoto from the North East? Called Enryakuji, it assisted troops belonging to a coalition opposing Nobunaga—so in 1571 he burnt the entire 3,000-building complex to the ground, earning himself the name ‘Devil King’.

Oda Nobunaga also used culture to show his power and authority. In particular, he was obsessed with the tea ceremony. Though tea had been introduced to Japan in the early Heian period—probably by Saichō or Kūkai when they returned from their travels in China—it had gone out of fashion alongside the general drift away from Chinese culture in the late 9th century. It was reintroduced three centuries later, perhaps by another monk, Yōsai, who planted Toganoō tea in the mountains north-west of Kyoto. This tea was matcha—unfermented, powdered green tea, made with a tea whisk. It spread in popularity during the Muromachi and Ashikaga periods, and became an importance aspect of warrior elite culture; the Muromachi warrior elite held tea-tasting contests in Kyoto, for example. Honcha (real tea) referred to this prized tea grown near Kyoto, while hicha referred to tea grown elsewhere.

The concept of monawase (comparisons of things) had been popular since the late Heian period, and both the Tale of Genji and Pillow Book describe courtiers comparing and judging various items. The contests of the Muromachi elite were different—far more serious. These games were transformed into serious pursuits: the way of tea, the way of incense (kodo), and the way of flowers. These are regarded as the three most important classical arts of Japanese culture. But it was not until the 15th century that the tea ceremony (cha-no-yu) would develop.

[Image idea: maybe take one from this news article https://matcha-jp.com/en/560 . Possible caption: Looking for a gift idea while in Kyoto? In the Heian period, nobles would burn incense while writing letters to infuse the message with a particular scent. At centuries-old shops like Kyukyo-do, you can buy the materials to write your own fancy ‘scented’ letter.]

The Tea Ceremony in Kyoto

The key feature of the tea ceremony was the influence of the wabi aesthetic. Heavily influenced by Zen Buddhism, it is hard to translate, but refers to a desirable austerity—that is, the understated beauty of simple, even imperfect objects. It is linked to the concept of sabi, and wabi-sabi as a worldview is based on the acceptance of impermanence and imperfection. So, in the tea ceremony, prized objects (meibutsu) were often simple, and to the untrained eye might seem to be of poor quality. Indeed, Alessandro Valignano, an Italian Jesuit who visited Japan multiple times in the 16th century, thought it was ‘totally unbelievable just how much appreciated these tools are. It is the kind of thing only the Japanese would understand’. Ironically, despite the focus on poverty and simplicity, the tea ceremony and its associated items were actually often extremely costly.

In reality, with enough time anyone can come to appreciate the beauty in these items—bowls (chawan), jars (chatsubo), caddies (chaire), and so on. Few, however, will ever match Nobunaga’s zeal. He relentlessly pursued the most sought-after utensils in what he called ‘meibutsu-gari’ (masterpiece hunting). Just as wearing European cloaks and drinking European wine illustrated his independence and power, so too did his lavish tea ceremonies, where he would show off his spoils and make people recognise his authority. This was a combination of cultural (bun) and military (bu) affirmation of rule.

Two of the temples at which he held these ceremonies can be visited in Kyoto today: Myokaku-ji and Shokoku-ji. Myokaku-ji is only ten minutes from Kurama-guchi station, and its garden is a wonderful place to see the cherry blossoms. One ceremony Nobunaga hosted here was led by Sen-no-Rikyū—perhaps the most famous tea ceremony master to have ever lived. Shokoku-ji was built in 1392 and is in the centre of Kyoto. Inside one of the halls is a ceiling painting Naki-ryu (Howling Dragon), called such because when you stand under it and clap your hands the echo sounds like a dragon howling. In the grounds you can also visit the Jotenkaku Museum. It’s rare for a temple to have a museum on its grounds, and this one is full of treasures: you can see zen-style calligraphy and ink paintings, as well as prized tea ceremony utensils—including a bamboo teaspoon carved by Rikyū himself.

There are also many opportunities for you to participate in a traditional tea ceremony yourself. Nowadays, tea from Uji is considered the best, and the area has many tea shops and houses where you can try Uji green tea. One is Taiho-An, which means ‘facing Phoenix House’—so named because it faces another of Kyoto’s UNESCO World Heritage Sites, Phoenix Hall. The main temple of the Byodo-in Monastery—the ‘temple of equality’—it was built in 1052-3, and you might recognise it from its depiction on the ten yen coin. Its guardian shrine is the nearby Ujigami Shrine, which you might remember from earlier. Unlike the bird it is named after, Phoenix Hall survived the fires that destroyed many of the other historical buildings in Kyoto. Byodo-in was built to create a ‘Land of Happiness’—the afterlife according to the Jodo sect of Buddhism. Its gardens and the beautiful art on display is all on that theme. Also on display is the sugata no byodoin, one of the most prized ancient temple bells in Japan.

Experience History in Style: Festival in Kyoto

If you’re not interested in the Tale of Genji or the tea ceremony, you might still want to visit the Ujigami Shrine on May 5th, because that’s when it holds its annual festival. In fact, Kyoto has many ancient festivals, which are wonderful ways to experience the city’s rich history and culture first hand.

There are three main festivals (matsuri) in Kyoto. The first is the Jidai Matsuri (Festival of the Ages), which is held on October 22nd and features a parade in traditional costume. It is held at Heian Jingu Shrine, which was built as a 5/8 scale replica of the Chōdōin, the main hall of the Imperial Palace from the late Heian period. It was built in 1895, though—like many historical buildings in Kyoto—was set on fire in 1976 and much of it burnt down. It was reconstructed a few years later, and can be entered from Jingu-do street. Passing through the Ohten-mon gate, you can wander through the shrine garden—if you can’t make the festival, in spring it is known for its cherry blossoms.

The second main festival is the Kamo Matsuri—now called Aoi Matsuri because of the hollyhock (aoi) leaves used for decoration. Held on May 15th, it is over 1,400 years old! Traditionally, the emperor would visit Shimogamo and Kamigamo Shrines to pray for a good harvest and peace; now, there is a magnificent procession from the Imperial Palace to Kamigamo shrine, with pageantry and costume. Even if you can’t make it to this ancient festival, you should definitely see Kamigamo and Shimogamo shrines. Linked by the Kamo river, together they are known as Kamosha, and are the oldest Shrines in Kyoto proper. Here, emperors of ages past worshipped and made offerings to their guardian spirits (ujigami). Kamigamo’s official name is Kamo-wake-ikazuchi Jini, from the divine power of thunder (ikazuchi) which is thought to drive away bad luck and protect from disaster. Here the Tango-no-Sekku (Boy’s Festival) is held every May 5th, which features the Kurabe-uma ritual—in which running horses chase away evil spirits. You can also try Yakimochi, which are toasted daifuku (sticky rice cakes with sweet bean paste) thought to be good for avoiding affairs. To be extra sure your marriage will be successful, you can also visit Aioi Shrine on the grounds of Shimogamo, which is dedicated to the god of good marriages. Here people pick up fortune slips based on lines from the Tale of Genji, and hope that their marriage will fare better than his…. You can also try matarashi dango, sticky rice balls covered in a sweet sauce. Though they were originally made as an offering for the shrine, these days you can keep them to yourself—after all, your stomach is just as important as your relationship!

To work off the calories from all these sweets, you might want to visit Shimogamo on January 4th, when a traditional kemari event is held. This is an ancient ball-passing game, imported from China 1,400 years ago and popularised during the Heian period; today, participants still dress as Heian nobility, while trying to keep the ball afloat. Of course, you could also see the Yabusame, a mounted archery ritual held on May 3rd. Also held in traditional Heian costume, participants shoot at targets while riding galloping horses and reenact Heian-era scenes. If you’re a fan of the clothes, you can visit a Heian costume studio, which let you try on traditional outfits, such as the 12-layered kimonos of court ladies—though be warned, this isn’t an easy instagram: it can take over two hours to complete all the makeup, dressing, and photography, and the more elaborate costumes are expensive—some experience packages add up to over 400,000 yen!

If the sound of that hurts your wallet, it might be best to experience Heian costume and culture in perhaps the grandest of the three festivals, the Gion Matsuri. Described as the most famous festival in Japan, the Gion Matsuri is held throughout July, and there are many festivities—though particularly impressive is the parade of floats (Yamaboko Junko) that processes through Kyoto on July 17th. Elaborately decorated, some of these floats are up to 25 metres tall, with wheels as big as people! In the days leading up this procession and a later second one, visitors can watch the construction of the floats and can even enter some. In the evenings, the city comes alive, with the streets full of food and drink vendors. Traditionally, during the festival families would display their treasures; today, near the start of the Gion Matsuri, during the Byōbu Matsuri (Folding Screen Festival), some notable local families continue this practice. They might display their family heirlooms—painted screens, kimonos, and other treasured artworks—in front of their houses. Some even let you enter! You should definitely take this chance, because the machiya—traditional wooden townhouses—are the defining characteristic of historic downtown Kyoto.

After all this excitement, it might be worth taking a trip to the shores of nearby Lake Biwa to visit Azuchi Castle. Built by Oda Nobunaga, he chose the location to enable him to keep a close eye on his capital while remaining far enough away to avoid the frequent fires and conflicts that often spread through the city. Nobunaga did not just want a functional castle—he wanted something to awe his followers and enemies. The first castle in Japan to be surrounded by high stone walls, the keep (tenshu) is seven stories tall. The 5th floor is octagonal—symbolising heaven—and is covered in gold leaf inside and out.

Japan United: The ‘Heroic Time’ in Kyoto

Sadly for Nobunaga, his impressive castle could not save him. In 1582, he was killed in what became known as the Incident at Honnō-ji. One day after hosting a tea ceremony at Honnō-ji temple, Nobunaga was betrayed by one of his generals, Akechi Mitsuhide. Nobunaga and his son were trapped in the ambush and committed seppuku (ritual suicide). Of course, no Kyoto conflict would be complete without a devastating fire, which not only destroyed many of the priceless meibutsu held at the temple, but resulted in Nobunaga’s remains never being found. Another mystery is Mitsuhide’s motive—no one really knows the reasons behind his betrayal.

Honnō-ji still exists in a different location; the current main hall, built in 1928, has a memorial tower for Nobunaga with displays of mementos and articles. There you can pay tribute to this titan of Japanese history and come up with your own theories for Mitsuhide’s betrayal—though Kyoto expert Sumiko Kajiyama recommends visiting Soken-in, a sub-temple of Daitoko-ji, for this purpose. Located in Kita-ku, Kyoto, Soken-in was founded as the mortuary temple for Nobunaga by his successor, Toyotomi Hideyoshi. Like most Kyoto landmarks, the current structure is not the original; it was rebuilt in 1926, though it does contain a seated wooden lacquered statue of Oda Nobunaga made in 1583.

Whatever you think about Mitsuhide’s betrayal, what is certain is that it didn’t end well for him. Hideyoshi quickly defeated him and completed the unification began by Nobunaga. Hideyoshi had, if anything, an ever greater enthusiasm for tea than Nobunaga, and it was under him that Rikyū rose to become Japan’s foremost man of culture.

In 1589, a donation from Hideyoshi enabled the construction of the romon (main gate) at Fushimi Inari Taishi, the head shrine of the kami Inari Ōkami. Short for ‘ine nari’ or ‘ine ni naru’ (reaping of rice), Inari is one of the principle kami in Shintō. In 711—decades before Kyoto was founded—Empress Genmei ordered Irogu no Hatanokimi to enshrine three deities on three mountains in the area. Traditionally, Inari was associated with agriculture, but today the shrine’s website describes the deity as one of ‘business prosperity, prosperity of industries, safety of households, safety in traffic and improvement in the performing arts’. Shrine texts describe Inari Ōkami as one ‘who feeds, clothes, and houses us and protects us so that all of us may live with abundance and pleasure.’

Sounds like one you should pay your respects to—and you can, by visiting the honden (main hall). Indeed, though the edifices are more recent (being last rebuilt in 1499), the shrine has been an important place of worship for over 1,300 years. The popularity of the enshrined deity is such that today some 30,000 ‘o-inari-san’ sub-shrines, associated with the head shrine in Kyoto, are dotted throughout Japan. By visiting, you’d be following in the footsteps of many important figures of Japanese history. For example, Sei Shonagon, the author of the Pillow Book, wrote about one visit she made, describing the climb to the shrine buildings as exhausting.

If that doesn’t put you off, the entrance to the hiking trail is at the back of the grounds. From there it takes a few hours to get all the way up the mountain and back, but the view of Kyoto is amazing—and, unlike Shonagon, you’ll have the option to take a break in one of several restaurants lining the path. Because Inari Ōkami is associated with foxes, they serve some fun food, like ‘Kitsune Udon’ (Fox Udon) or aburaage, a fried tofu dish said to be a favourite treat of foxes. Also different is the fact that the path up the mountain is now lined with many red torii gateways. From the Edo period, the shrine became popular with merchants, and it became a custom to donate a torii gateway express prayers and appreciation. The senbon torii (thousand torii gateways) is one of the most iconic sights in Kyoto—definitely not one to miss. Their vermilion colour is most striking; traditional Japanese beliefs attach great power to the colour. It was thought to attract evil influences, drawing it away from individuals. Ake, the word for vermillion, can be written in different characters, each with different meanings—including red in dawn or light. The brightness and hope in these meanings is associated with belief in the soul of Inari Ōkami.

Hideyoshi also adopted the Prince Hachijō Toshihito, who built the Katsura Imperial Villa. Its garden is said to be the most perfect ever designed, with tea ceremony houses carefully positioned to maximise appreciation of seasonally changing plants and views. It is possible to book tours of the garden by appointment, and there you can imagine the Prince sitting on his Moon-Viewing Porch, sipping green tea.

This brief time period—from Nobunaga’s entry into Kyoto in 1568 to 1600—is known as the Azuchi-Momoyama period, named for the castles of Nobunaga and Hideyoshi respectively. It was a time of dynamic and bursting art—described as an ‘heroic time’, with larger-than-life historical figures leading Japan into the early modern period. It would come to an end with the victory of Tokugawa Ieyasu over his rivals. He ruled from Edo (now Tokyo), declaring it the administrative capital, though Kyoto was still the sacred city, the heart of Japan. Recovering from the devastation of the civil wars, Kyoto was seen as the cultural and spiritual centre of the nation, and the daimyō usually maintained residences in both ‘capitals’.

The Edo Period: Kyoto’s Floating World

This marked the beginning of the Edo period, which only increased the flowering of culture—a renaissance. The new Shogun ordered massive building programs, funded by his defeated rivals, to show his power. One must-see example is Nijō Castle, another of Kyoto’s World Heritage Sites. If you’re interested in feudal Japan, the buildings within Nijō’s massive grounds are probably the best surviving example of the castle architecture of that era. They are open to the public, and feature English audio guides. The main attraction, Ninomaru Palace, was the residence of the Shogun while he visited Kyoto. Perhaps because of the multiple walls and moats of defence, it survives in its original form, and its multiple separate buildings are connected by corridors with infamous ‘nightingale floors’—called as such because they squeak when stepped on, as a security measure against intruders. So remember, if your floors squeak, you don’t need to worry—you can just tell people you have an old Japanese method for detecting potential burglars (or assassins).

In the Edo period, the government tried to keep a strong distinction between ‘high’ and ‘low’ arts. Noh, for example, was in many ways the private playground of the noble (kuge) and military (buke) classes. In contrast, the masses enjoyed Kabuki theatre, jōruri puppet dramas, street fairs, corner storytellers, and other forms of entertainment.

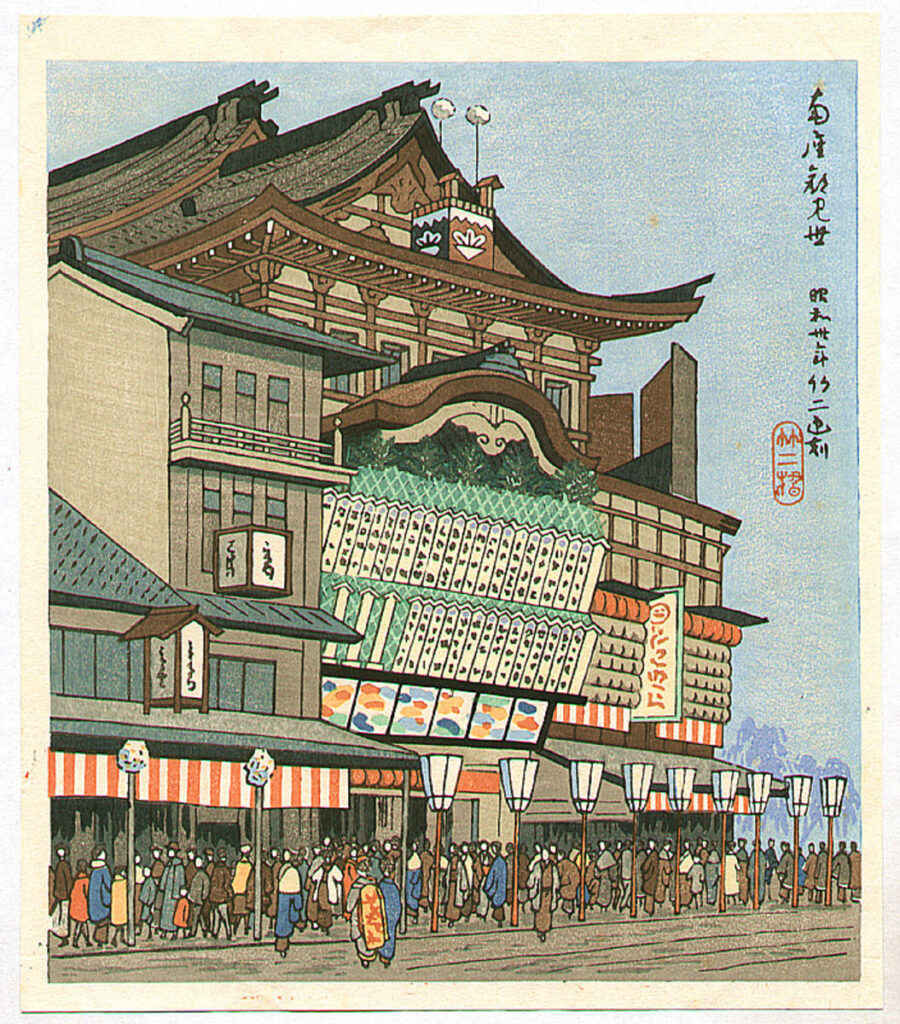

Merchants, in particular, were at the bottom of the Confucian social hierarchy, and therefore were often banned from displaying their wealth in the form of houses or clothes. They therefore turned to the pleasures of the ‘floating world’. This included Kabuki: started at the beginning of the Edo period, it was first performed by courtesans—yūjo (women of pleasure, prostitutes)—attempting to attract and entertain customers. In 1629, however, women were eventually banned, and from then on performances were done by all-male groups. Though it peaked in popularity in the 18th century, you can still see kabuki plays today; if you do, look out for the elaborate costumes and distinctive makeup—with its oshiroi (white powder) base and exaggerated lines creating the appearance of animal or supernatural masks.

The oshiroi foundation was also made famous by Geisha; not prostitutes, they were actually explicitly banned from selling sex (though many still did). In this way they were separate from yūjo. Around the start of the Edo period prostitution was banned outside of specific pleasure quarters—though inside of them, Yūjo were licensed and allowed to operate. One such area in Kyoto was Shimabura; in the 18th century, a new pleasure quarter emerged in Gion, and it was here that Geisha began to appear. Though historically male Geisha performed a role similar to that of European court jesters, by 1800 the profession was understood as female. They quickly grew in popularity, though throughout the Edo they often could not work outside the pleasure districts. Geisha were—and are—hired entertainers known for their conversation and hosting skills, as well as their ability on traditional instruments like the shimasen.

Though the number of Geisha in Kyoto fell during the 20th century, you can still be entertained by them today. Currently there are five hanamachi (Geisha districts, literally ‘flower town’). Gion is still active, though Shimabura is now more of a living museum—a few trained women play the old traditional role of the tayū (the highest rank of courtesan), and tourists can see their presentations of music, dance, and tea ceremony at one of the two preserved historic buildings in the area. To see Geisha in person, you might visit a Kyoto teahouse, or attend one of the four spring shows in the hanamachi. One is the Miyako Odori, performed four times a day throughout April at the Gion Kōbu Kaburen-jo theatre near the Yasaka Shrine. A central part of Kyoto culture, you can watch 32 maiko and geiko (less and more experienced Geisha) dance, often in unison with 20 musicians in identical costumes. Nearby Maruyama Park is a popular location for cherry blossom viewing in April, but if you’re brave enough to be visiting Kyoto during the cold winter weather, Yasaka Shrine hosts traditional New Year rituals and celebrations.

If you’re unable to plunge into Kyoto’s floating world, you can experience it second-hand by viewing and appreciating ukiyo-e. Literally meaning ‘pictures of the floating world’, ukiyo-e is a genre of art that flourished during the Edo period. Most famous for its woodblock prints, artists in this style depicted a variety of subjects: from female beauties, to sumo wrestlers, to scenes from historical or folk talks, to nature, to erotica. Prints and paintings showing scenes from the hedonistic floating world were especially popular with the merchant classes taking part in the pleasures of that world themselves. You’ll probably be familiar with the most internationally famous example, Great Wave Off Kanagawa by Hokusai. You might also have seen another popular work of his, the infamous The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife. But he also made prints depicting scenes from Miyako, the capital. Indeed, scenes from Kyoto were a popular subject for ukiyo-e artists.

Another less well known form of art important in Kyoto was that of ningyō (dolls). Unlike in the west, where dolls are seen mainly as children’s toys, in Japan ningyō had a variety of functions and were often expensive and treasured family heirlooms. Like the Geisha and kabuki actors, these dolls often had bright white ‘skin’ created from gofun. Made from oysters, during the Edo period gofun production was centered in Edokawachi, Kyoto, and it was also used in Buddhist sculptures and Noh masks. One type of doll that was popular during this period was the gosho-ningyō (palace doll), celebrations of youth and innocence that depicted children. Specifically popular was a subtype called saga-ningyō, named in the Meiji period after the Saga area near Kyoto where it was believed these dolls were originally made. This area was also celebrated for saga-bon (books from Saga), illustrated deluxe editions of stories like the Tale of Genji that exploded in popularity at the beginning of the Edo period. They are credited with being part of a revival of the ‘courtly aesthetic’ that is associated with art produced in Kyoto. Another speciality of Kyoto artists were menhaburi gosho, a type of mechanical doll with a mask; like a Noh actor, the mask could be raised to cover the face, transforming the gosho into the character on the mask.

The ninth princess of Emperor Go-Sai was a fan of ningyō, and took some with her when she entered the imperial nunnery at Donge’in. Some of them are still in its collection, and you can visit the temple today; while it’s not open to the public, if you’re a temple stamp collector you can still get a red stamp in your Temple stamp book. Next door is Rokuo-in temple—less famous than its neighbour, Tenryu-ji, it is a good place to see in Autumn; the path from the main gate at Rokuo-in is lined with maple trees that explode into brilliant colours. Though the spring blossom is more famous, many visitor guides claim Kyoto is even more beautiful during this later season. Rokuo-in is also a shukubo (temple lodging) for women; if you’re an early riser, you can take part in the morning sermon and zazen session at 6.30am, and dinner and a bath is included. Just don’t fall into the same mistake as some English-speaking tourists, who confuse it with the Rokuon-ji (Deer Garden Temple, the official name for the Golden Pavilion)!

Tenryu-ji is famous for a reason, though. Built in 1339, it was once an enormous complex with over 100 sub-temples. Only a few remain—Hogon-in and Kogenji are worth seeing, but are only open to visitors for a limited time in spring and autumn. The real reason to visit, however, is the garden, one of the least-changed and most beautiful of Japan’s traditional landscaped gardens. Its creation is credited to the first head of the temple, the master gardener Muso Soseki. His design used the surrounding landscape, a technique called shakkei; reflecting the shifting seasons, a large pond is in the middle and two nearby hills form part of the composition.

From the temple’s side gate you can approach Arashiyama Bamboo Grove. Strolling through the majestic green corridors of bamboo is free, but you can also rent a bike or hire a rickshaw—the last option might be the most pricey, but the driver will also explain the history of the grove and the landmarks within it. On the other hand, if you prefer independence, exercise, or a heavier wallet, you can follow ‘Inside Kyoto’s’ walking tour, available for free online. With that extra money you can definitely afford the admission fee for Okochi-Sanso Villa, which you’ll reach at the top of the grove. A nice, usually-uncrowded alternative to the Imperial villas, you’ll be able to enjoy gardens and majestic views of the city. The fee also includes a Japanese sweet and hot matcha tea—a perfect reward for the walk! Alternatively, if you’re feeling particularly single, you can drop into Nonomiya Shrine in another part of the grove and join the young women praying for a love match.

If you can’t come in March or November, brave the winter and experience Hanatoro (flower and light road), an illumination event that takes place in December in Arashiyama. During the event the streets are lined with thousands of lanterns, flowers, and light displays, and the temples and shrines are illuminated. Particularly beautiful in the lights, though, are the bamboo forest and the iconic Togetsu-kyo Bridge.

Togetsu-kyo Bridge, which you might recognise if you watch Japanese period films, was first built in 836. Togetsu, meaning moon crossing, comes from Emperor Kameyama of the Kamakura period; during a boat party, he thought the full moon looked as if it was crossing the bridge. Here you can enjoy the splendid views of the Katsura River and Arashiyama Mountain. During Hanatoro the mountainside is also illuminated, and when it snows the area looks like a work of art; in March and November the cherry blossoms and fall colours are, of course, particularly wonderful.

If you feel pulled by the sound of the mountains (Kawabata, anyone…?) or your visit to Nonomiya Shrine was particularly successful, you could take the Kameoka Sagano Scenic Romance Train. Departing from Saga Torokko Station (next to JR Saga-Arashiyama Station), a leisurely 25 minute journey takes you through some of the longest tunnels in Kyoto and winds alongside the picturesque Hozukyo Ravine. You can hop off at a station halfway and explore a national park, or stay on until the train arrives at the resort town of Kameoka. If you choose, you can return to Kyoto by boat. The Hozugawa Kudari is a river cruise in traditional small boats—be warned, though, it’s not all smooth sailing, as you will have to traverse some rapids on your way back to the ancient capital.

Of course, these days no one will stop you from entering the city. But in the Edo period, most of Japan was closed to foreigners. (Though right now Coronavirus restrictions are bringing this tradition back…) The third shogun, Tokugawa Iemitsu, began this policy of total isolation. Interestingly, he also wanted to keep another group of people out of Kyoto in particular: the daimyō. He wanted to break daimyō connections to the imperial court and refocus their attentions to the new administrative capital in Edo. To achieve this, he made sankin-kōtai (alternate attendance) compulsory. Under this system daimyō were forced to alternate living in their domain and Edo, which reduced the chance of them starting wars or growing wealthy and powerful far away from the shogun’s control. To demonstrate his power, in 1634—the year before the sankin-kōtai was made compulsory for some of the daimyōs—Iemitsu entered Kyoto with over 300,000 men. He would be the last shogun to visit the ancient capital for over 200 years.

Old School ‘Virtual Tours’ of Kyoto

Nevertheless, during this time guidebooks were produced for some of the major cities in Japan, with Kyoto leading the charge They were written in easily understandable common characters, to be read by common travellers. By the mid-18th century guidebooks singled out 88, then over 300, especially noteworthy places in the ancient capital. So don’t feel intimidated by the fact that you’d never be able to see every sight or get a stamp from every one of the 1,600 temples in your temple book. It’s a problem travellers have had for centuries! However, these books were not actually to help people visiting the city; instead, they were a sort of pre-internet, pre-photography form of virtual travel—a way for people to experience the capital from the comfort of their own home. Though travel was much harder (and slower) in these times, the early Edo period was marked by great developments in the road system, in large part because of the requirement that daimyō move home every year. Like Rome, the roads linked the country to Edo: the two main routes connecting the administrative capital to the ancient capital were the Tōkaidō route along the sea and the Nakasendō trail through the mountains of central Japan. If you have time, travelling part of these routes—experiencing the beauty of Japan’s nature and visiting the hundreds of small towns and villages that line the routes—is a must. However, they were a very popular subject for ukiyo-e, so if you don’t have time you can always partake in a little old-school virtual travelling of your own.

Back then, legend stressed the importance of the three great cities, the santo: Kyoto, Osaka, and Edo. Kyoto was supposedly famed for water, mushrooms, temples, women, textiles, and bean curd; its artisans and merchants; and its aristocrats, imperial court, temple priests, and private scholars and doctors. Japan in 1700 was one of the most urban societies in the world; Edo was the largest city in the world, and Kyoto—with about 350,000 residents—was easily comparable to London or Paris.

Power Shifts Back to Kyoto: The End of the Shogunate and the Problem of the Barbarians

Despite the fact they were supposed to stay out, the daimyō kept a strong interest in Kyoto. By the mid-19th century, as the Tokugawa shogunate faced ever more problems, daimyō attention began to seriously shift from Edo back to the ancient capital. One of the main causes of the problems facing the Tokugawa shogunate was that of foreigners. In 1858, America had forced Japan to open its borders, but many were demanding that the shogunate drive out the ‘barbarians’. Though Kyoto had been kept mostly off limits to foreigners even after the opening, powerful figures in the court there were loudly displeased at the various treaties made with western powers. Emperor Kōmei himself was anti-foreign and refused to support the bafuku. By 1862, the city was becoming a centre of loyalist intrigue, filled with energetic, anti-foreign samurai willing to fight and die for their emperor and their nation.

The bafuku’s control was slipping; its decision in the same year that it had no choice but to institute some reforms—such as ending the alternate attendance and allowing the daimyō to spend the saved money on their armies and navies—led to it losing more control.

In 1863, the Emperor was convinced to formally request that the shogun expel the Western barbarians. This prompted the young shogun, Tokugawa Iemochi, to visit Kyoto—but the difference from the last such visit was stark. Where as in 1634 Iemitsu had made the emperor call on him at Nijō Castle, Iemochi went personally to the emperor. It was clear that the shogunate was losing power. This visit was a key moment in the shift of political power back to Kyoto, and more and more daimyō began setting up headquarters there. Indeed, through political manoeuvring, the shogun was forced by anti-foreigner daimyō to accept the request, and committed to expelling the barbarians by June 25 of that year.

Most were aware that this could not be done, and indeed the date passed with no action from the bafuku. Loyalist forces in Chōshū, however, took matters into their own hands and fired on American and French ships, which quickly retaliated. Militarily and economically powerful westerners, at the height of their imperial and colonial empires, were angered by these and other attacks. After a brief conflict in which the loyalists marched on Kyoto, the bafuku emerged victorious.

The next few years saw the bafuku desperately attempt to push through modernising reforms and retain control over the restless country. But their victory over the loyalists was not complete—provincial lords had experienced a taste of power and wanted more, and samurai had consolidated their military strength. Importantly, for the first time in 250 years peasants were given a chance to take up arms and join battle. Eventually, the bafuku took action against the loyalists again—but this time, the domain of Tosa managed to convince Chōshū and Satsuma, historic enemies, to join forces in rebellion.

By this time Kyoto had become so important that the last shogun, Tokugawa Yoshinobu, spent his entire period of office in the Kyoto area—never once feeling free enough to take time to return to Edo.

The Capital Moves From Kyoto: Modernisation in the Meiji Period

After another relatively brief conflict, the combined loyalist forces were successful this time, and took Kyoto in 1867; the next year Emperor Meiji made a formal declaration of his power. This was the Meiji Restoration—the start of the Meiji period. The young new emperor conducted a triumphant parade from Kyoto to Edo, which was renamed Tōkyō—the Eastern Capital. The palace of the former shogun in Tokyo became the new home of the imperial family.

The following decades saw a breathtakingly fast modernisation. Though many argue that the Restoration itself changed little outside of the political system in Kyoto and Tokyo, this rapid change was nothing short of revolutionary. From the armed forces, to railways, to industrial factories, to education—even to things like the postal system—Japan borrowed and learned from the west, becoming a global power faster than any thought possible.

All this change was not without resistance. In 1869, for example, samurai enraged at the prospect of conscription assassinated a top politician in Kyoto. Violent resistance to other government policies broke out at various points in many cities, including the capital of peace and tranquility. And the government could not decide whether to keep the emperor in Tokyo or send him (and therefore the capital) back to Kyoto—the decision was only made permanent in 1889.

The change in capital prompted Kyoto to undergo its own program of modernisation. In 1890, the Lake Biwa canal was completed, and the first hydroelectric power plant serving the general populace in Japan was built in the northeastern area of the city a few years later. By 1895, streetcars were transporting passengers across Kyoto, and just two years later it became home to Japan’s second oldest university.

Not all benefitted, however. As Japan became a colonial power, discrimination and suppression became more rigidly enforced. Koreans faced often violent racism, and opposition groups such as socialists who criticised the decisions of the government also faced violent and harsh crackdowns. Another group that suffered was the burakumin. In the past, people who had worked in jobs that Buddhist thinking marked as polluted—mostly around the slaughter of cows—were shunned as outcasts. Though they had been officially liberated by the reforms at the beginning of the Meiji era, their descendants still faced much discrimination. There were around 500,000 burakumin in the early 20th century, and the largest numbers were concentrated around Kyoto and nearby Osaka. In 1922 some burakumin formed the Suiheisha (Levellers Association), confronting those accused of discrimination, sometimes violently. One important activist, Asada Zennosuke, known as the ‘Doctrinal Leader of Buraku Liberation’, was from Kyoto. The government responded by cracking down, and during WWII the group was disbanded under pressure from the military government. It was later re-formed as the Buraku Liberation League.

Most people in Japan were relatively unconcerned with the plight of these minorities. Indeed, the first decades of the 20th century were filled with energy and excitement. Kyoto, as one of the major cities in the growing nation, was a centre of intellectual and academic debate. In the 1930s, the major question was still Japan’s position in the world. One group of philosophers of the Kyoto school formed what was called the ‘Kyoto faction’, arguing that war was necessary to determine national culture. In fact, the ‘philosophy of world history’ that they attempted to construct was in reality a justification for continuing Japanese aggression and imperialism. Their arguments and beliefs came closest of any group to defining the boundaries of Japanese fascism.

Indeed, as the Second World War raged, most intellectuals enthusiastically supported the war. Many produced speeches, essays, and art as part of a great effort to ‘overcome modernity’—a general attack on Western culture. This movement reached its peak in July 1942, when Kyoto University hosted a famous conference on ‘overcoming modernity’. Those present saw themselves as part of an intellectual battle against Western thinking that was just as important as the physical battle against Western dominance in Asia. In reality, overcoming modernity was impossible—in part because things like baseball and jazz were simply too popular to get rid of.

Modern Kyoto

In the years after the war, Japan experienced another period of rapid growth. As it has throughout the country’s history, the eternal city played an important role. For example, in 1997 the Kyoto Protocol was adopted in the city. Called the most significant environmental treaty ever negotiated, it called for 41 countries and the European Union to reduce their emissions of greenhouse gases to 5.2 percent below 1990 levels between 2008-12.

These days, some wonder if Kyoto is in danger of too much ‘modernity’—they talk of concrete slowly taking over the city, destroying the beauty of the traditional far more permanently than any fire could. They worry about the disappearance of the machiya and other ancient parts of the Kyoto character.

On one hand, this means you should visit as soon as possible! But really, in many ways the combination of modern and traditional is a major positive. You can arrive at the brand new Kyoto Station, travel in old street cars, and bike through bamboo forests. You can even travel back in time—to the glorious Heian period during the festival parades, mighty fuedal era at the castles, or modernising Meiji by exploring Saga-Toriimoto Preserved Street. You can stay in comfortable new hotels, peaceful ryokans (inns), or even converted machiya. You can learn about history at one of over fifty museums, see it first hand at the hundreds of Shintō shrines, thousand Buddhist Temples, 17 World Heritage Sites, and more. You can end the day by enjoying some sake, a traditional industry in the capital, or you could support a modern industry and visit the Kyoani & Do Shop, selling products from the famous Kyoto Animation studio.

In fact, Kyoto is so full of things to do, see, and experience, no one could ever hope to write about it all—let alone visit it. But is it really a surprise that the eternal city—the city of a thousand temples—is anything but empty? The only thing to do is to dive in and experience it for yourself. Hopefully this more modern ‘virtual guidebook’ has let you do that to some extent—and has made you eager to discover more.